At Tianjin Port, thousands of containers bound for Mongolia wait, not for hours or days, but months. The growing demand for containerized trade between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Mongolia is being strangled by a severe infrastructure bottleneck. The result? Congestion, delay, and economic loss across the PRC–Mongolia corridor. The logjam at Tianjin was actually a symptom of the constraints in processing the containers at Zamiin-Uud and Ulaanbaatar.

The PRC–Mongolia trade corridor has become a vital route for containerized freight in the Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation (CAREC) region. Container movements through Zamiin-Uud have grown significantly, reaching 339,494 TEUs in 2023, up from 152,471 in 2018. Yet, even as demand increases, the corridor is buckling under pressure.

As of August 2024, over 5,100 containers were stranded at Tianjin Port, awaiting onward rail shipment to Mongolia. The situation deteriorated further by September, with 7,000 TEUs stuck at port, some waiting 90 to 120 days to reach Ulaanbaatar. While rail capacity between Tianjin and Erenhot is robust, the bottleneck lies at Zamiin-Uud, where only 7 trains per day can be processed.

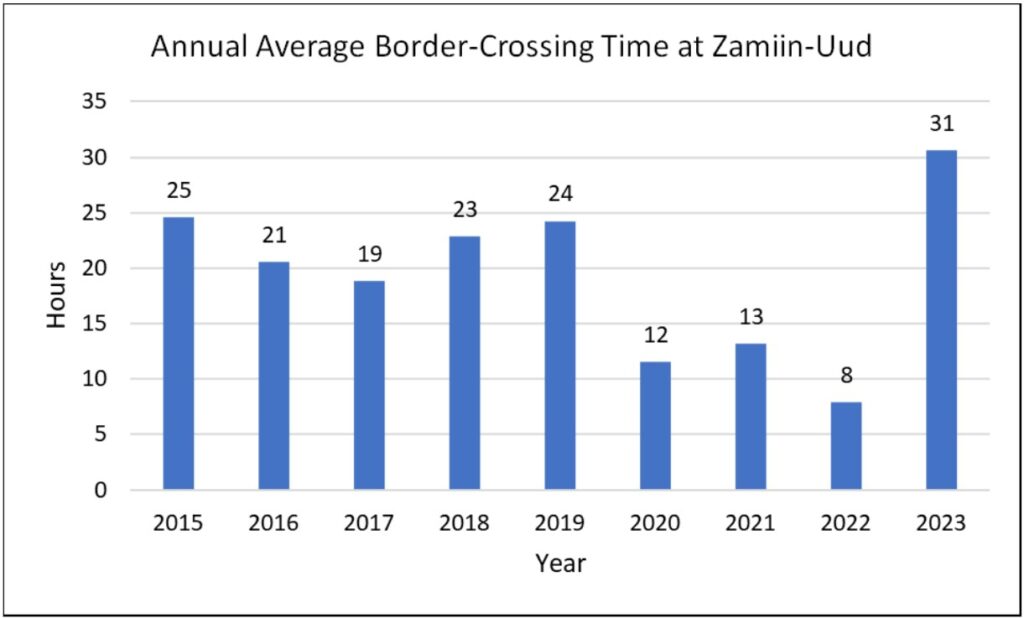

In the period 2015 to 2023, the average border-crossing time at Zamiin-Uud hovered at 20 hours. There was a reduction in the COVID years as volume of freight were affected, but the time surged in 2023 as international trade resumed and PRC removed its strict zero tolerance policy. That year, the estimated border-crossing time shot to 31 hours, reaching an all-time high.

First Bottleneck: Zamiin Uud BCP

Both countries use different rail gauges (PRC 1,435 mm and Mongolia 1,520 mm). At the border, the BCP that receives incoming trains need to perform a gauge change operation. As such, Zamiin Uud BCP handles the operation, managed by Ulaanbaatar Railways (UBTZ). UBTZ operates four terminals in the BCP, but the throughput is affected by these constraints.

- Yard cranes not operational and becoming “white elephants”.

- Limited number of mobile cranes.

- Manual process of tracking the containers during the gauge change process, using MS Excel spreadsheets instead of a proper Terminal Operating System (TOS).

Second Bottleneck: Ulaanbaatar

Onward from Zamiin-Uud, the inefficiencies continue: Ulaanbaatar has 14 outdated container stations, each able to handle just 1–2 trains per day. The dispersed location of separate container stations result in sub-optimal use of land space and urban traffic congestion. It is also difficult for the existing stations to expand physically as they are located in the city. In addition, the station operators are hesitant to modernize the materials handling equipment. There has been some discussions about relocating all the existing stations to a new logistics parks at the outskirts of the city, but the government has not confirm the location and the timeline.

These bottlenecks are not just logistical. Thy have severe economic repercussions too. Long delays increase supply chain costs, strain relationships between traders and logistics operators, and deter new trade and investment into the corridor. The backlog is especially problematic given Mongolia’s increasing use of containers for exports and domestic shipments. This is also the sole trunk corridor for Mongolian economy, where the 1,000 km long rail track connects essential goods to key cities such as Ulaanbaatar, Choyr, Erdenet, Sainshand and Sukhbaatar.

Solving the congestion crisis requires targeted infrastructure and institutional reforms. First, Zamiin-Uud’s transshipment capacity must be urgently upgraded. This includes

- Increasing the number of mobile cranes

- repairing idle yard cranes,

- expanding yard space,

- replacing manual data entry with an automated terminal operating system.

These steps would speed up the gauge-change operations critical for cross-border rail transfers.

Second, consolidating Ulaanbaatar’s fragmented container terminals into a single dry port equipped with modern cranes and IT systems will improve handling capacity and efficiency. Currently, the 14 scattered terminals lack economies of scale and use outdated equipment, leading to duplication and underutilization of resources.

Finally, policy clarity is essential. The Mongolian government must finalize the location and development plan for the new dry port to enable private investment. Without it, logistics providers remain hesitant to commit capital, prolonging the status quo.

Despite growing awareness, multiple challenges persist. At Zamiin-Uud, yard cranes remain non-functional, likely due to maintenance and financing issues. Operators resort to less efficient mobile cranes, which require more labor and incur higher costs. Moreover, manual Excel-based container tracking slows operations and increases human error.

Ulaanbaatar’s fragmented terminals suffer from lack of investment due to uncertainty. While a dry port at the outskirt of the city has been proposed, no formal plan or government directive has been issued, leaving private operators in limbo. As a result, container handling remains slow and inconsistent.

Even adding more trains from Tianjin is not a viable solution in the short term, it would only worsen the backlog at Zamiin-Uud without parallel investments in handling capacity. The cost of inaction is mounting, with supply chains disrupted and trade opportunities lost.

ADB, through its TA6694 REG: Containerization in the CAREC Region, has spotlighted the PRC–Mongolia corridor’s urgent needs. The study recommends modernizing Zamiin-Uud’s transshipment yards, improving yard layout, restoring cranes, and deploying a container information system. It also proposes finalizing the logistics park at Ulaanbaatar, enabling private investment in container handling infrastructure.

ADB is also encouraging dialogue between policymakers, customs, and railway companies to resolve operational inefficiencies and clarify long-term development plans. These efforts align with ADB’s broader CAREC agenda to improve cross-border transport, promote multimodal logistics, and strengthen regional trade integration.

With technical assistance and stakeholder engagement, ADB aims to turn this corridor from a choke point into a model of efficiency.

If unresolved, the Tianjin–Zamiin-Uud–Ulaanbaatar bottleneck will continue to erode Mongolia’s competitiveness and deter regional trade. Longer delivery times and rising costs are already pushing traders to seek alternative (and often less efficient) routes.

However, with targeted upgrades, especially at Zamiin-Uud and Ulaanbaatar, the corridor could become a high-performing container artery in the heart of Asia. Investments in cranes, systems, and coordination could slash delivery times, improve reliability, and unlock Mongolia’s potential as a regional logistics hub.

It’s time to shift gears from diagnosing the problem to implementing the fix. With coordinated action by governments, ADB, and the private sector, the container jam along the PRC–Mongolia route can become a story of transformation, not stagnation.