The CPMM analysis relies on consistent and comparable data across CAREC countries, despite their inherent differences. This chapter provides an update of the main developments and CPMM data at a national level for each CAREC member country to help explain the trends or resulting outcomes at the regional or corridor level. This country-level analysis examines the policies, regulations, infrastructure, and institutional factors that can affect corridor performance. Pertinent barriers and issues are highlighted, key developments and progress are noted, and high-level recommendations are included.

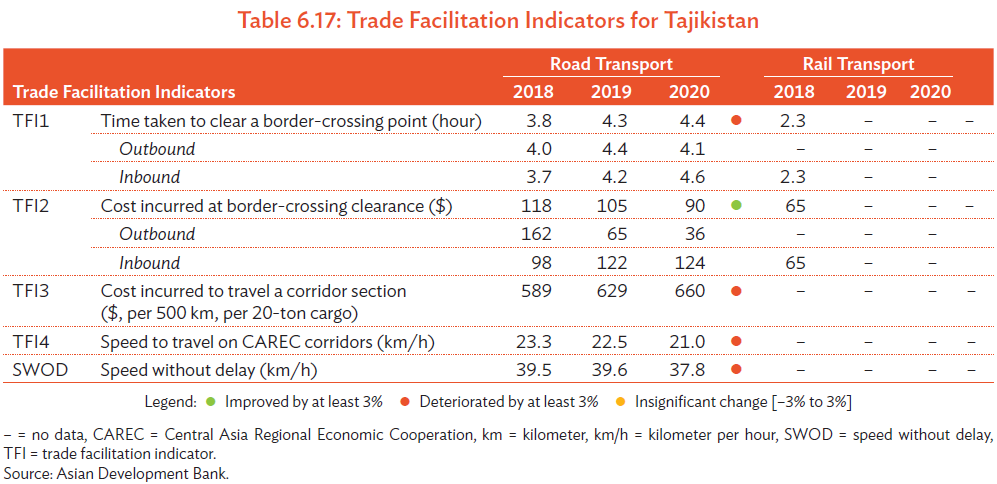

The 2020 CPMM report introduces the four TFIs at the country level, segregated by road and rail transport, and further separated into outbound and inbound direction for border-crossing time and costs (Tables 6.1–6.22). These data are supplemented by average border-crossing time and cost for BCPs along relevant CAREC corridors. Key CPMM findings, updated trends and developments, and country-specific recommendations are also provided in this chapter.

Key Findings

- Average border-crossing time was unchanged, estimated to be 4.3 hours in 2019 and 4.4 hours in 2020. However, the inbound and outbound traffic exhibited a divergent outcome. Outbound traffic had a minor increase to 4.1 hours in 2020, while inbound traffic averaged 4.6 hours in 2020, an increase due to more stringent sanitation and health checks.

- Border-crossing costs declined from $105 in 2019 to $90 in 2020. Total cost increased from $629 in 2019 to $660 in 2020.

- SWOD dropped from 39.6 km/h in 2019 to 37.8 km/h, while SWD dropped from 22.5 km/h to 21.0 km/h.

- Border-crossing time at Dusti was the most time-consuming, taking 13.8 hours for outbound traffic and 4.0 hours in inbound traffic in 2020. Inbound traffic at Panji Poyon was also time-consuming at 4.8 hours.

Trends and Developments

Tajikistan was a prime beneficiary when the new administration in Uzbekistan liberalized trade and transit regimes. Cooperation with neighboring countries did not stop despite COVID-19, although border agencies adopted stricter measures. The government imposed the provisional procedure for regulating international transit as ordered by the President on 16 March 2020 (No. 1k/25-2) and the Prime Minister (No. 2k/20-25) under the framework of prevention of COVID-19 in Tajikistan. The Ministry of Transport approved the “Temporary Regulation of International Freight Road Transport in Tajikistan” on 2 April 2020. This regulation applies to import, export, and transit of goods. The regulation stipulated these conditions:

- Entry of foreign drivers and vehicles is only allowed at border terminals or customs control zones.

- The goods must be shipped by domestic carriers from the border to the inland destination.

- The State Unitary Enterprise of Automobile Transport and Logistics Services as well as the State Transport Control and Regulation Service are designated to ensure adequate supply domestic vehicles to move goods from border to inland destinations.

- Trailers and semitrailers are permitted to move beyond the border terminals or customs control zones.

- Shipment of strategic items such as humanitarian aid could be granted exception to be sent in foreign vehicles but would need to be escorted to the final destination.

- Customs clearance is conducted at the border terminals.

- Sanitation is required for all amenities at the border, including hotels, restaurants and cafes, toilets, and shower rooms.

High-traffic BCPs at Bratsvo, Fotehobod, and Guliston were operational throughout the crisis. Kulma Pass was closed from 20 March and reopened on 30 May 2020. The Kulma BCP is located at the Tajikistan–PRC border and was halted partly due to winter and high altitude, and partly to halt the spread of COVID-19 from the PRC. There was no abrupt or severe impact to the trade facilitation indicators.

In 2020, Tajikistan launched an AEO program. This initiative was supported by the International Trade Center (ITC) which allows shippers and transport operators to utilize a simplified process for cross-border trade. Qualified companies would enjoy shorter processing time under customs controls, as well as customs clearance at specific premises preapproved by Customs.

Recommendations

- Intensify the development of the Shymkent–Tashkent–Khujand corridor. ADB has supported the study of the Shymkent–Tashkent–Khujand corridor in recent years, which is an important transit corridor linking Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. The trade potential is limited by existing poor secondary roads (e.g., Khujand to Asht), lack of test laboratories and regulations on entry quotas, and fees that inhibit cross-border movement of vehicles. A joint master plan could be developed between the three countries that identifies the gaps and proposes actions to remove or lower the barriers to cross-border trade.

- Replace customs escort with smart tracking technologies. Tajikistan customs imposes mandatory customs escort fees for transit shipments, even for TIR operations. This costs $2 for every 10 km. This fee is translated to approximately $54 for Dusti to Panji Poyon, or $113.80 for Jalgan to Panji Poyon. Many CAREC countries have already eliminated mandatory customs escort (except for a small list of commodities such as dangerous goods or oversized cargoes). Smart tags on customs seals which use GPS that report real-time location status could be adopted, potentially alleviating the need for customs officers to escort the shipments.

- Provision of X-ray scanners for Tajikistan customs. There is a shortage of X-ray machines to carry out item inspections at the BCPs. The use of X-ray scanners and equipment would expedite the inspection process and thus shorten average border-crossing time. It is further recommended that Panji Poyon BCP be prioritized to operate such equipment due to smuggling and security concerns on freight that originates or transits from Afghanistan. It is also suggested that Dusti BCP be assigned importance to this, as the average customs controls took 4 hours, relatively higher than other BCPs in the Central Asian republics.

- Set-up green lanes at border-crossing points to facilitate transit trade. Tajikistan can attract transit trade between Central Asia and South Asia. To move freight between Afghanistan and Kazakhstan or the Kyrgyz Republic, a shipper can either route through Tajikistan or the Kyrgyz Republic. When the International Security Assistance Forces were based in Manas, Kyrgyz Republic was a very vibrant transit trade route for commercial and military goods flowing from the Kyrgyz Republic to Tajikistan to Afghanistan. Things have changed significantly since 2016, and Uzbekistan has liberalized many rules and regulations. Tajikistan, a beneficiary of this liberalization, also would face competition in the transit trade, particularly given the planned Uzbekistan–Afghanistan–Pakistan railway project. To simplify border-crossing, Tajikistan could designate green lanes at Gulistan and Panji Poyon so that freight from Central Asia and South Asia could move more rapidly. This is particularly important given that Afghanistan targets Kazakhstan as a potential attractive market for its agricultural produce.

- Mutual recognition of authorized economic operators. Tajikistan launched AEO in 2020. The next step is to harmonize AEO criteria and agree to mutual standards so that Tajikistan companies also enjoy a simplified process in neighboring countries. For instance, qualified Tajikistan transport operators could access green lanes at designated BCPs in another country, without the need to queue with other vehicles.