The CPMM analysis relies on consistent and comparable data across CAREC countries, despite their inherent differences. This chapter provides an update of the main developments and CPMM data at a national level for each CAREC member country to help explain the trends or resulting outcomes at the regional or corridor level. This country-level analysis examines the policies, regulations, infrastructure, and institutional factors that can affect corridor performance. Pertinent barriers and issues are highlighted, key developments and progress are noted, and high-level recommendations are included.

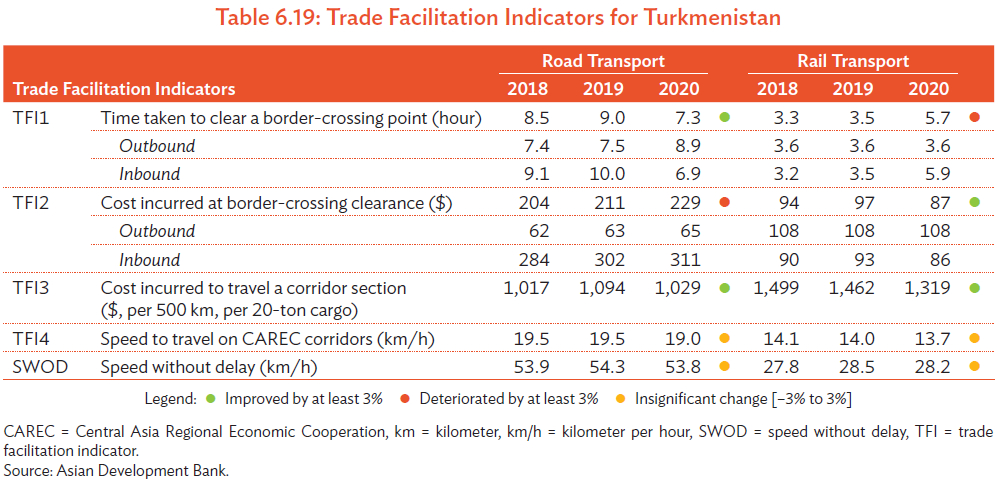

The 2020 CPMM report introduces the four TFIs at the country level, segregated by road and rail transport, and further separated into outbound and inbound direction for border-crossing time and costs (Tables 6.1–6.22). These data are supplemented by average border-crossing time and cost for BCPs along relevant CAREC corridors. Key CPMM findings, updated trends and developments, and country-specific recommendations are also provided in this chapter.

Key Findings

- For road transport, average border-crossing time decreased from 9.0 hours in 2019 to 7.3 hours in 2020. This seeming improvement was in part due to the closure of borders to foreign trucks, which reduced the waiting time.

- The average border-crossing cost for road transport in 2020 increased slightly from $211 in 2019 to $229, while total transport cost dipped from $1,094 to $1,029 in the same period.

- SWOD reached 53.8 km/h in 2020, and SWD attained 19.0 km/h. Both speeds for road transport were relatively unchanged year-on-year.

- Rail transport continued operations despite the shutdown of road transport. The increased freight diverted to trains caused a noticeable jump in average border-crossing time from 3.5 hours in 2019 to 5.7 hours in 2020.

- Border-crossing cost changed from $97 in 2019 to $87 in 2020, and total transport cost changed from $1,462 to $1,319.

- Both SWOD and SWD were comparatively unchanged for rail transport, reaching 28.2 km/h and 13.0 km/h, respectively.

- Trucks crossing Farap took 9.4 hours (outbound) and 10.9 hours (inbound) for 2020. Trains took 21.4 hours in 2020, a huge increase from 2.7 hours in 2020. This was partly caused by the station handling increased rail freight, as well as an isolated sample that experienced a 120-hour delay attributed to documentary errors.

Trends and Developments

The Government of Turkmenistan closed its border to foreign trucks on 23 March 2020. Garabogaz BCP

(at the Kazakhstan border) and Farap BCP (at the Uzbekistan border) were subsequently reopened.

However, shipments entering Turkmenistan must be transloaded from foreign trucks into Turkmen trucks

without contact at designated areas on the border.

Foreign trucks arriving in Turkmenbashi International Seaport on 23 March 2020 or earlier could leave their trailers or semitrailers in the designated areas of the port for pick-up by Turkmen carriers for in-country delivery or transit through its territory. Afterward, foreign tractors must return, with the driver, by sea to the originating port. However, after 23 March 2020, all cargo to Turkmenbashi Port must be sent in trailers or semitrailers without tractors and drivers.

Turkmenistan essentially shut its border to foreign trucks, as foreign carriers cannot forge interline agreements with Turkmen carriers (to which they can entrust both the cargo and equipment) during such a short adjustment period. Central Asian road carriers that previously transited through Turkmenistan to reach Iran (e.g., Bandar Abbas port) had to cease operations. Currently, rail is the only available transportation option through Turkmenistan to Iran. This has caused an increase in rail traffic, with 30–80 wagons transported daily.

Recommendations

- Participate in regional and international bodies. To assert influence and integrate into international trade and transport, Turkmenistan could do more by participating in established bodies. Currently, Turkmenistan is not represented in the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route, where Azerbaijan, the PRC, Georgia, and Kazakhstan are active members.

- Modernization of Farap border-crossing point. Farap is an important gateway for transit, connecting cargo flow between seaports such as Bandar Abbas with Uzbekistan. In addition, this BCP serves both road and rail traffic. CPMM observed that Farap is consistently one of the more time-consuming road BCPs, and this is attributed to limitations in infrastructure, procedure, and equipment. The authorities could review the current situation and determine the appropriate solutions.

- Limited and gradual relaxation of visa restrictions. CPMM samples show that Caucasus and Central Asia shipment are done through Azerbaijan (Baku) to Kazakhstan (Kuryk). Transport operators often avoid Turkmenistan due to restrictive visa procedures and transit regime. Naturally it is not wise to ease visa requirements during these COVID-19 times, but the country could consider selective relaxation and adoption of risk-based programs such as mutually recognized AEO programs with neighboring countries.

- Enhance logistics capacity through training programs. Modern logistics is a relatively new concept. To realize the ambition of multimodal transport and increased efficiency to support international trade, it is imperative to raise the professional capacity of the personnel working in this industry. The government could support accredited programs run by reputable firms in the form of skills development funds. For instance, the Turkmenistan Logistics Association is a member of the International Federation of Freight Forwarders Associations (FIATA),34 and could offer national certification programs on international freight forwarding, particularly on the use of FIATA documents such as the multimodal transport waybill.