The CPMM analysis relies on consistent and comparable data across CAREC countries, despite their inherent differences. This chapter provides an update of the main developments and CPMM data at a national level for each CAREC member country to help explain the trends or resulting outcomes at the regional or corridor level. This country-level analysis examines the policies, regulations, infrastructure, and institutional factors that can affect corridor performance. Pertinent barriers and issues are highlighted, key developments and progress are noted, and high-level recommendations are included.

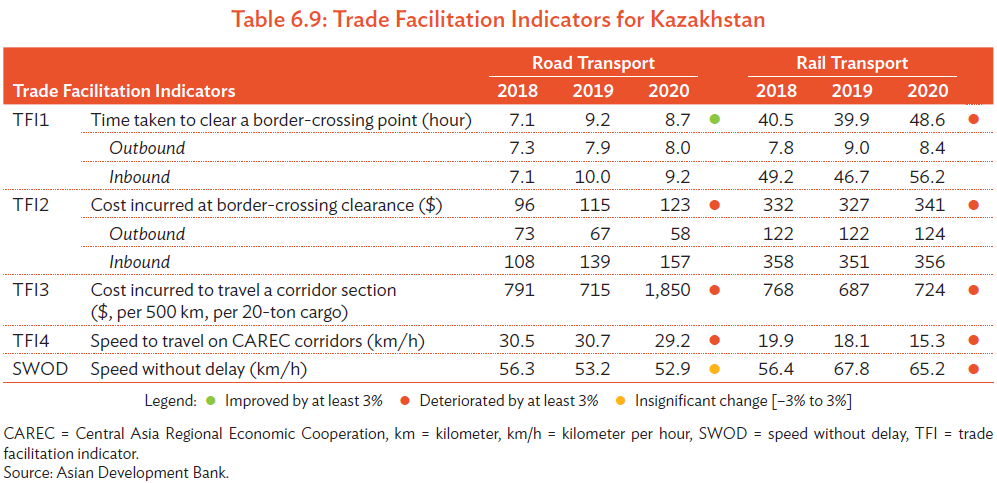

The 2020 CPMM report introduces the four TFIs at the country level, segregated by road and rail transport, and further separated into outbound and inbound direction for border-crossing time and costs (Tables 6.1–6.22). These data are supplemented by average border-crossing time and cost for BCPs along relevant CAREC corridors. Key CPMM findings, updated trends and developments, and country-specific recommendations are also provided in this chapter.

Key Findings

- In 2020, a stark contrast between the performance of road and rail transport was observed, caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Freight was diverted from road to rail as BCPs at the beginning of the outbreak in an effort to contain the spread of the disease.

- For road transport, the average border-crossing time shortened slightly from 9.2 hours in 2019 to 8.7 hours in 2020. While border-crossing cost increased from $115 to $123 in the same period, total transport cost surged nearly 2.5 times from $715 in 2019 to $1,850 in 2020, reflecting the capacity constraints of trucking and drivers. SWOD averaged 52.9 km/h and SWD was estimated to be 29.2 km/h, in line with the 2019 results.

- For rail transport, the negative impact on time was more pronounced unlike road transport. Border-crossing time jumped from 39.9 hours in 2019 to 48.6 hours in 2020, a 21% increase. Border-crossing cost increased slightly from $327 in 2019 to $341 in 2020, while total transport cost increased from $687 to $724. SWOD was 65.2 km/h, in line with 2019 estimates, while SWD dropped considerably from 18.1 km/h to 15.3 km/h due to the lengthened border-crossing time delay. The border delay was a confluence of different reasons, due to increased freight volume diverted from roads, existing capacity constraints, and additional sanitation controls imposed by the Chinese authorities in Q4 2020, creating a spike in the border-crossing duration as queues developed at the border.

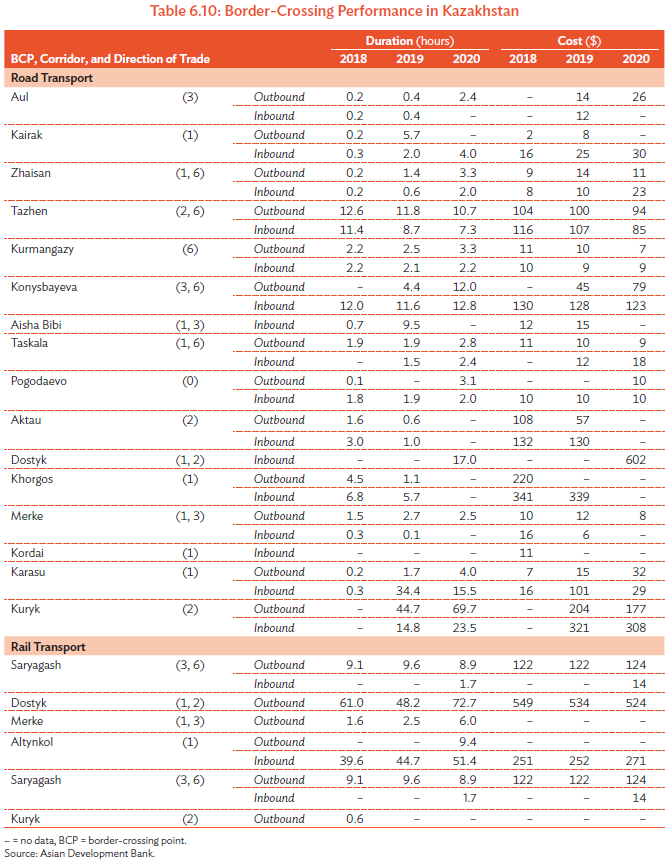

- Road BCPs such as Konysbaeva and Tazhen were identified to be significantly more

time-consuming. A notable concern was detected at Kuryk, where estimates of outbound traffic

averaged 69.7 hours to clear formalities and inbound traffic required 23.5 hours. - Rail BCPs at Dostyk reported 72.7 hours for border-crossing, followed by Altynkol at 51.4 hours,

both showing a considerable increase from 2019 estimates.

Trends and Developments

The year 2020 was challenging for many countries, and without exception Kazakhstan was also affected. While Kazakhstan’s gross domestic product dropped 2.6%, the transport sector plunged 17.2%. Freight tonnage for all transport modes decreased 6.6% and freight turnover decreased by 4% year-on-year. Air transport was particularly affected as international and domestic flights were canceled during the pandemic and were slow to recover. Trucks at Nur Zholy suffered from long queues when the PRC authorities imposed stringent sanitation inspection. The parking area in Khorgos Dry Port now serves as a waiting point for the trucks crossing the border to relieve the traffic congestion that plagued Kazakhstan transport operators at the end of 2020.

Rail transport was a rare bright spot in the challenging times, keeping the cross-border trade bustling when road BCPs and airports were closed. In 2020, 876,000 twenty-foot equivalent units (TEU) from the PRC to Europe passed through Kazakhstan, a 36% increase from 2019. Like road transport, trains faced a surge in border-crossing time at the end of 2020. While the PRC and Kazakhstan held dialogues in December 2020 and January 2021 to resolve the congestion, long-term plans are being initiated to modernize the rail transport sector. The Dostyk–Aktogai–Mointy rail infrastructure is being modernized with a capacity to serve 1 million TEUs. Another positive development was the increase of container traffic across the Caspian Sea. In 2020, 12,434 TEUs were transported from Kuryk to Baku, a 32.6% increase from 2019.

Kazakhstan’s efforts to combat COVID-19 also involved innovative solutions. The government rapidly implemented online access to essential services such as banking to minimize human contact points. In particular, the processing of shipping documents necessary for international trade and transport was automated. An important achievement is the broadening awareness and adoption of www.elicense.kz28 to allow online transmission and approval of permits for international road freight. The payment of customs duties and taxes for transit shipment was also automated, and a transport operator now receives an electronic notification to confirm that payment has been received by the authorities.

As the largest landlocked country in the CAREC region, Kazakhstan’s inland waterways have strategic potential which could be developed for transit. Kazakhstan President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev signed the “On Ratification of the Shipping Treaty” on 17 November 2020. This treaty aims to encourage the development of water transport within the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) and simplifies the licensing procedure for the transit of vessels along the inland waterways within the EAEU territory. Once in force, Kazakhstan transport operators will have access to a simplified transit regime to use inland waterways for freight transportation in the Russian Federation, an advantage that other Caspian Sea countries (Azerbaijan, Iran, and Turkmenistan) do not possess. This would attract overseas operators to work with Kazakhstan companies for transit through the Russian Federation using inland waterways, which would be very cost-effective compared to road transport, and even rail transport. Two corridors are of interest here. First, freight from the Black Sea is transported to Kazakhstan seaports via the Volga–Don canal. The treaty can increase the transit volume through Kuryk. The second corridor is the Irtysh River that courses through the PRC, Kazakhstan, and the Russian Federation leading to the Kara Sea. The projected freight volume is expected to increase from 879,000 tons in 2020 to 1.5 million tons in 2025.

Recommendations

- Revision of the Law for Transportation of Shipments by Railways. Amendments on the railway laws are ongoing. This is instrumental to resolving the existing issues and problems between the consignee, consignor, carrier, and asset owner (locomotive or wagon), who are responsible in terms of deploying the wagon to the specific station or collecting wagons for the next shipment. As shown in CPMM, wagon availability is still an ongoing concern for the rail transport.

- Pilot of CAREC Advanced Transit System. Similar to the previous recommendation, countries participating in CATS/ICE pilot test are expected to benefit from the project. The participation of Kazakhstan also allows the possibility of extension to other major trading partners for the CAREC countries.

- Encourage containerization. As described below, the growth of container traffic despite the pandemic has been impressive. Those use-cases where container traffic has been more pronounced lie in multimodal transport, such as rail–water across the Caspian Sea. A comprehensive “containerization” master plan developed by international and national experts could be crafted to address the legislation, regulatory, and operational issues. In many reports, experts note that this plan might face two fundamental issues in Kazakhstan, as well as in other Central Asian republics. Firstly, the transport economics may not favor containerization. If a shipment is domestic and unimodal, use of containers may not be cost-effective. A 20-foot container holds 15 tons, and a 40-foot container holds 25 tons, compared to a standard wagon that holds 60 tons.29 The cost per ton to use a container is high. Secondly, border officers such as customs would need to be conversant with the international maritime conventions and the documents related to the use of sea containers. Thirdly, containers from major shipping lines would demand a quick return of the containers and are usually reluctant for a container to travel far inland. These factors must be considered in the plan to encourage containerization.

- Analyze the feasibility and implementation of e-CMR. The International Road Transport Union (IRU) is leading and coordinating the acceptance and implementation of digitalization of TIR and CMR, and many countries in CAREC region have embarked on these. It is recommended that Kazakhstan policy makers and the national TIR association KazA to analyze the viability and ramifications of the Additional Protocol to CMR 2008 (e-CMR) and design an implementation road map. This is expected to involve intensive legislation, regulatory, standardization, digitalization, and harmonization, for instance, in terms of aligning this convention with the transit regime and liability guarantees mechanism in the EAEU.

- Develop inland waterways. The shipping treaty opens new opportunities for the Kuryk terminal in terms of serving transit, and offers a cost-effective mode to send freight using Kazakhstan-registered vessels to Volga–Don canal and Irtysh River. On the other hand, planning and development of the resources such as the infrastructure, rolling stocks, and technical and operational personnel are necessary to fully capitalize on the opportunities. Developing a master plan for inland waterways transport can be useful to guide policy makers and attract private investment.