The CPMM analysis relies on consistent and comparable data across CAREC countries, despite their inherent differences. This chapter provides an update of the main developments and CPMM data at a national level for each CAREC member country to help explain the trends or resulting outcomes at the regional or corridor level. This country-level analysis examines the policies, regulations, infrastructure, and institutional factors that can affect corridor performance. Pertinent barriers and issues are highlighted, key developments and progress are noted, and high-level recommendations are included.

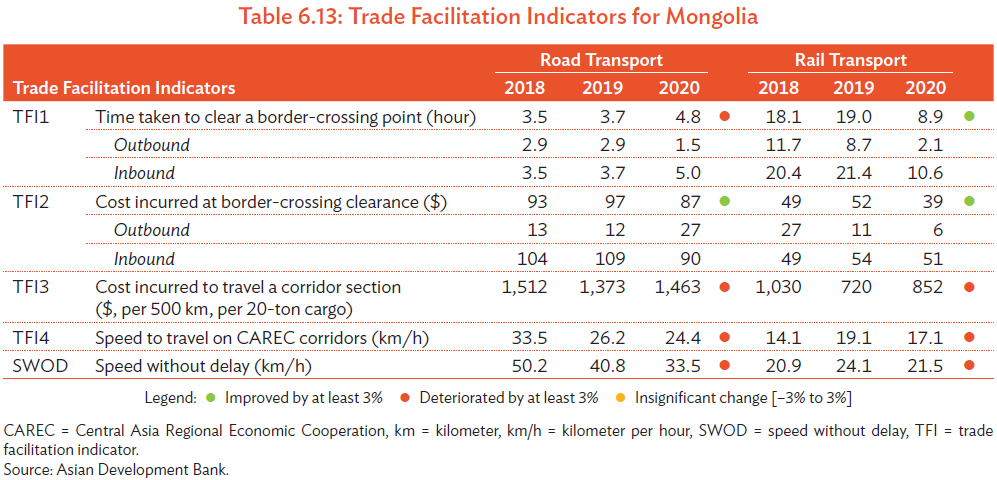

The 2020 CPMM report introduces the four TFIs at the country level, segregated by road and rail transport, and further separated into outbound and inbound direction for border-crossing time and costs (Tables 6.1–6.22). These data are supplemented by average border-crossing time and cost for BCPs along relevant CAREC corridors. Key CPMM findings, updated trends and developments, and country-specific recommendations are also provided in this chapter.

Key Findings

- In 2020, average border-crossing time at road transport suffered an increase from 3.7 hours in 2019 to 4.8 hours in 2020. This was due to prolonged delays for inbound traffic to comply with health and sanitation controls.

- Average border-crossing cost declined slightly from $97 to $87 but total transport cost increased

- from $1,373 in 2019 to $1,463 in 2020. This increase in road freight rate echoed the patterns observed in other countries as shippers grappled with the problem of finding transport operators, who had to work under reduced capacity and additional fees associated with health and sanitation.

- Both SWOD and SWD dropped. From 2019 to 2020, SWOD changed from 40.8 km/h to 33.5 km/h, while SWD slid from 26.2 km/h to 24.4 km/h.

- For rail BCP, the average border-crossing time reported a sizable drop from 18 hours in 2019 to 8.9 hours in 2020. In contrast to road transport, the inbound traffic declined from 21.4 hours in 2019 to 10.6 hours in 2020.

- Average border-crossing cost dropped from $52 in 2019 to $39 in 2020. However, total transport cost increased from $720 in 2019 to $852 in 2020.

- Both SWOD and SWD declined. SWOD dropped from 19.1 km/h in 2019 to 17.1 km/h in 2020, and SWD decreased from 24.1 km/h in 2019 to 21.5 km/h in 2020.

Trends and Developments

Since Mongolia borders the PRC, the government adopted measures early. The State Special Commission announced general measures to stall the spread of COVID-19 on 10 February 2020, and the General State Inspection Agency ordered disinfection and other measures on 13 March 2020. There was no restriction enforced on domestic movement of people and freight. The Mongolia Customs General Authority determined that selected items would need to be handled and cleared at inland customs offices, such as raw and processed meat. As such, bonded carriers would be activated to escort the truck to the inland customs offices. Since all commercial airlines were canceled during the pandemic, this severely reduced air carriage capacity for flying goods in and out of Mongolia, and diverted freight to land-based transportation.

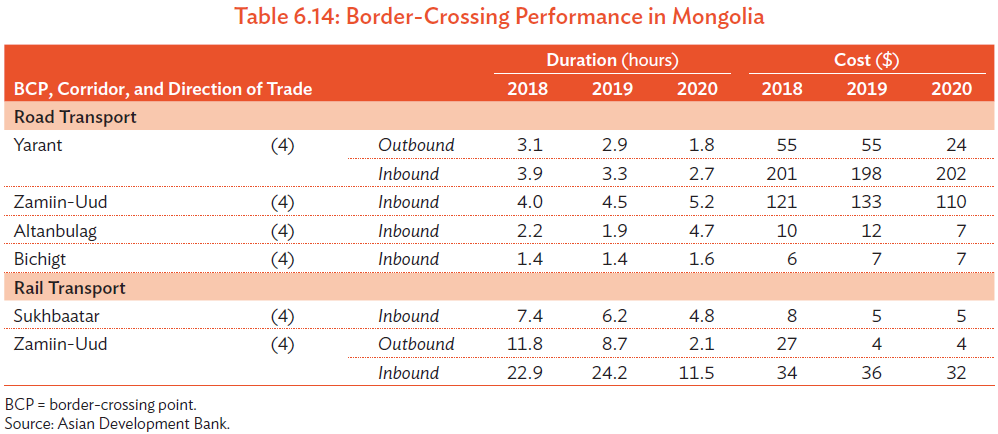

High-traffic BCPs at Zamiin-Uud and Sukhbaatar remained fully open throughout the first half of 2020. Road BCPs at Altanbulag, Borshoo, and Zamiin-Uud continued operations. However, Bichigt was not operational as the PRC closed the adjacent border. During the epidemic, freight flow remained open, but the borders were closed to the passage of passengers. The PRC trucks could not enter Mongolia, so goods must be transloaded at the “no man’s land” on Mongolian trucks.

Recommendations

- Develop a national railways master plan. There is an urgent need to increase the capacity for rail freight. This plan driven by policy makers will aim at practical measures and incentives to lift carriage capacity, and covers areas such as infrastructure, operations, capacity building, quality management system, economic study, and financial projects. Technical assistance by ADB for instance will be extremely useful. A review of the organizational and operational performance of UBTZ is also essential since it is the national rail carrier.

- Increase number of freight wagons. The increased demand for freight is already affecting rail performance. The estimated SWODs from 2017 to 2020 showed that this speed hit the lowest at 18.4 km/h in 2020. SWD was even lower at 13.5 km/h due to border-crossing delays and wagon shortages. There is an urgent need to increase availability of freight wagons by procuring new wagons and strengthening the working condition of existing wagons through an effective maintenance program.

- Promote transit Mongolia. This is a national program that was launched in the early 2000s and succeeded in promoting attention and awareness on the transit potential of Mongolia. Then, transit was only possible using rail, but now it is also possible to use highways, though the former is still dominant. There is little detail and promotion on this program now, and not even a functional website is available to announce updates. Such an initiative, much like the Nurly Zhol program in Kazakhstan, is instrumental to provide a development road map for the country and attracts much needed investment.

- Intensify development of Zamiin-Uud Free Zone. The work on Zamiin-Uud Free Zone, which commenced in 1995, has not proceeded as planned. Infrastructural gaps, legislation reforms, and procedures modernization are needed. This is especially true as CPMM estimated that the total transport cost (road) along subcorridor 4b amounted to $1,576 (ranked third most costly among 17 CAREC subcorridors) and rail amounted to $1,017 (ranked second among six subcorridors). ADB has approved a $30 million loan to develop this free zone and hopefully reduce cost of trade. However, there is still much planning required for transport and logistics zones, and how multimodal transport and warehousing can operate at this location.