The concluding chapter analyzes the performance of Torkham BCP, a vital hub in Pakistan’s terrestrial trade with Afghanistan and Central Asia channeling significant volumes of both passenger and freight traffic. Torkham plays a crucial role in facilitating existing transit traffic, including road transport associated with Afghanistan Transit Trade (ATT) and routes to Central Asia, as well as the prospective trilateral rail corridor linking Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Uzbekistan. This chapter examines the current capacity and performance of Torkham BCP and related issues and provides insights and recommendations. The case study examines the Pakistan side of Torkham only.

Profile of Torkham BCP

Geography and History

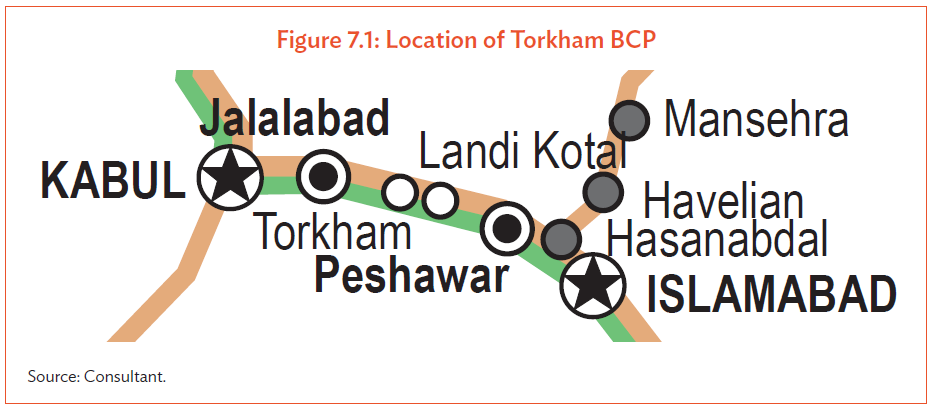

Torkham BCP is situated at the Afghanistan-Pakistan border, approximately 54 km and an 1.5-hour drive from Peshawar, the nearest city. Peshawar’s proximity positions Torkham as a transport hub for goods between Afghanistan and other regions. Goods in transit from southern ports and exports from other Pakistani cities converge in Peshawar prior to their movement to the BCP. Similarly, goods imported or in transit from Afghanistan are collected here before proceeding to their final destination.

Torkham BCP began operations with the establishment of the Durand Line in 1893. In July 2019, the BCP began 24-hour operations as policymakers from Kabul and Islamabad sought to alleviate congestion and significant crossing delays. Recognized as one of the most time-intensive BCPs in the CAREC region, Torkham’s sub-optimal layout, inadequate handling capacity due to insufficient equipment and scanners, lack of segregation between passenger and freight traffic, and inefficient border-crossing procedures are attributed for the delays. A significant contributing factor was the existence of numerous police checkpoints along the 55-km stretch between the border stations of Afghanistan and Pakistan, where trucks were required to halt for physical inspections by security personnel. This led to a high level of corruption, as transport operators paid varied sums to secure advantageous positions in the queue or receive expedited treatment during inspections. Following the Taliban’s takeover of Kabul in August 2021, border crossing durations decreased as corrupt officials departed the country.

Physical Layout

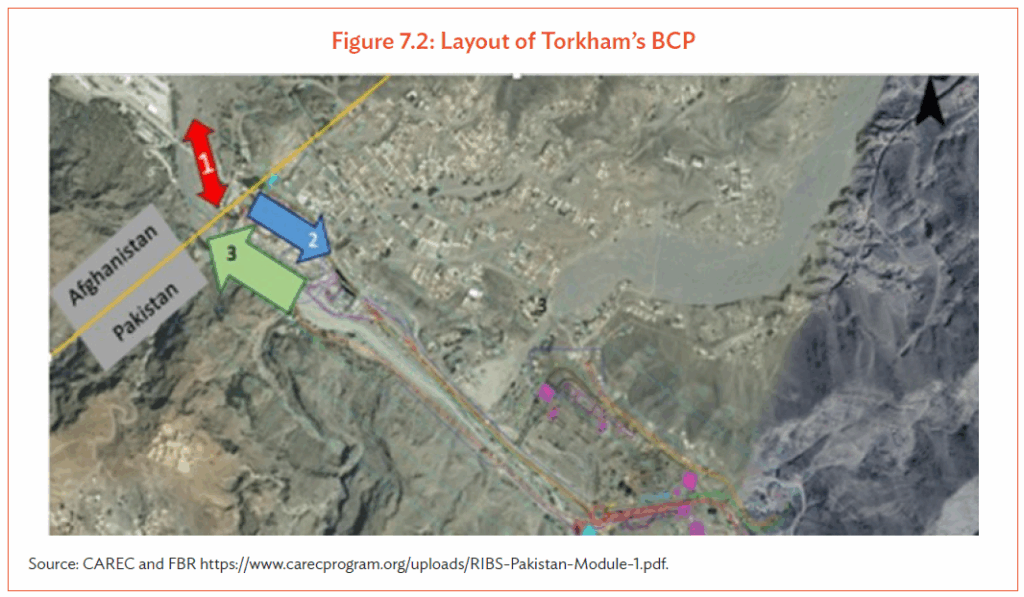

Torkham BCP is situated in the mountainous Khyber Valley region. A single public road links the highway to Torkham BCP. In Pakistan, there are five lanes designated for vehicle movement: three lanes for outbound traffic and two lanes for inbound traffic. The Afghanistan side has a single lane for vehicles traveling in both directions, constrained by a solitary bridge, which further limits the width of the road shoulder. The design capacity for outbound traffic is 1,200 vehicles per day, and 550 vehicles per day for inbound traffic.

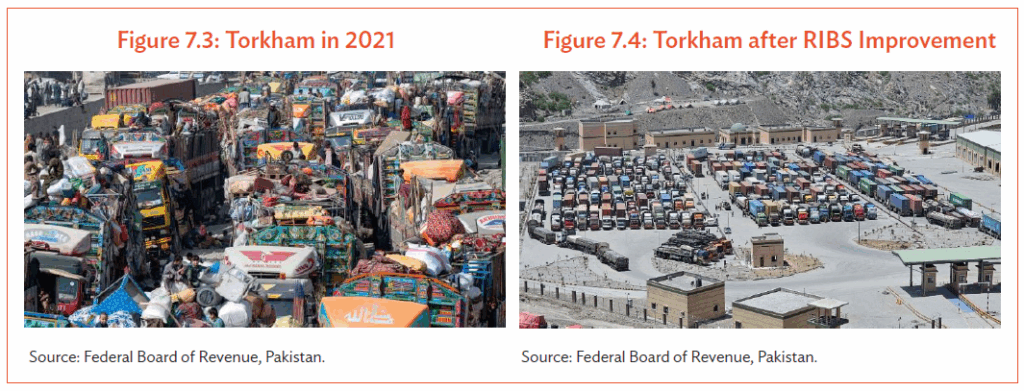

Before RIBS, there was no parking facility for heavy transport vehicles. Trucks queued outside the BCP in a very disorganized manner. The new design after RIBS offers a dedicated parking space for vehicles.

Design Capacity

The annual design capacity of Torkham BCP is 110,000 trucks, with a maximum capacity of 127,000 trucks. Freight movements from Pakistan to Afghanistan constitute 50% of the traffic, with transit accounting for 35% and imports for 15%. The infrastructure at Torkham is optimized to accommodate increased truck traffic from Peshawar in Pakistan to Jalalabad and Kabul in Afghanistan. Due to Afghanistan’s significant reliance on imports, transit shipments proceed from Pakistan to Afghanistan. 1

Table 7.1: Design Capacity of Torkham BCP (number of trucks per year)

| Direction of Trade | Annual Design Capacity | Maximum Capacity |

|---|---|---|

| Import | 16,500 | 19,050 |

| Export | 55,000 | 63,500 |

| Transit | 38,500 | 44,450 |

| Total | 110,000 | 127,000 |

Stakeholders

Due to the critical significance of the Torkham BCP, multiple border agencies operate here, showcasing a complex institutional landscape.

Table 7.2: Border Agencies and Responsibilities at Torkham BCP

| Agency | Key Responsibilities |

|---|---|

| Pakistan Customs | • Clearance of import/export goods – Inspection and examination – Processing transit cargo – Revenue collection |

| Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) | • Immigration control (entry/exit of persons) – Human trafficking prevention – Visa/stay permit checks |

| National Logistics Cell (NLC) | • Terminal management – Cargo handling – Warehousing – Support to border operations |

| Frontier Corps/Pakistan Army | • Security of the border crossing – Coordination with Afghan border forces – Monitoring of sensitive areas |

| Anti-Narcotics Force (ANF) | • Narcotics and contraband control – Search and seizure operations |

| Quarantine Department | • Sanitary and phytosanitary checks – Certification of agricultural/food products |

| Animal Quarantine Department | • Health inspections of live animals – Issuance of animal health certificates |

| Plant Protection Department | • Inspection of plants/plant products – Pest control compliance |

| Health Department | • Health screenings (especially during outbreaks) – Issuance of health certificates |

BCP Performance

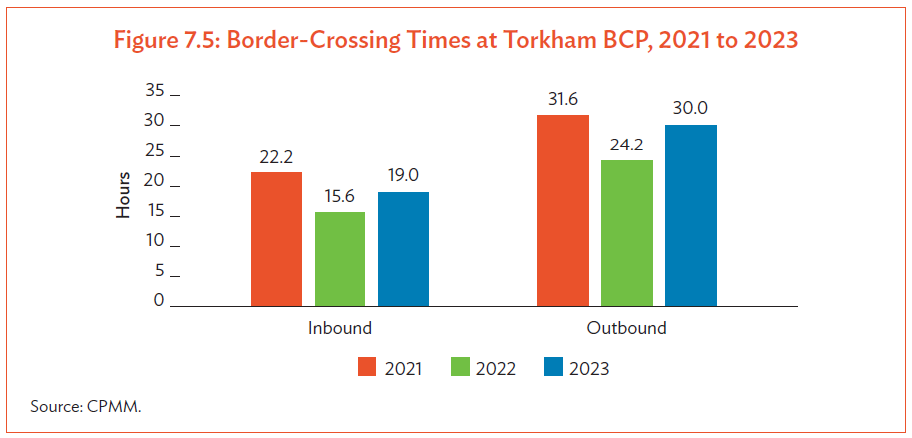

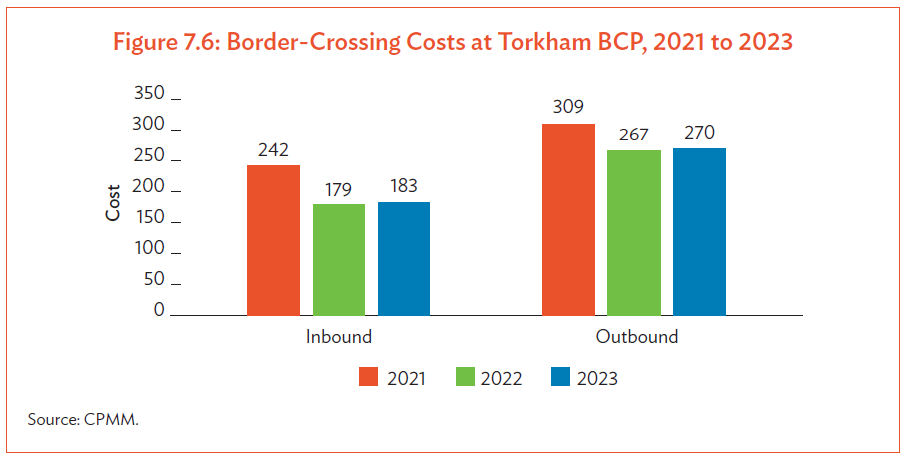

The border-crossing duration at Torkham indicates that shipments experienced extended completion times on the Pakistan side (outbound) during 2021–2023, varying approximately from 31.6 hr to 30.0 hr. The average duration increased by 24%, from 24.2 hr in 2022 to 30.0 hr in 2023. The bordercrossing time for inbound traffic was shorter, ranging from 15.6 hr to 22.2 hr during the same period. Border-crossing time increased by 22%, rising from 15.6 hr in 2022 to 19.0 hr in 2023. Both inbound and outbound shipments at Torkham BCP showed a year-on-year increase. Its recent performance shows an improvement over 2021, when strict border controls were implemented as a result of COVID-19 measures. Border-crossing cost at Torkham exhibits a similar pattern, ranging from $179 to $242 for inbound, and $267 to $309 for outbound. Between 2022 and 2023, the costs remained almost steady. For inbound, the cost increased 2% from $179 in 2022 to $183 in 2023, while the cost for outbound increased 1% from $267 in 2022 to $270 in 2023.

Issues

The Torkham BCP, while essential for regional trade, suffers from various operational, physical, and institutional challenges that compromise its reliability. Inadequate task execution and disparities in accessibility impede the smooth facilitation of cross-border trade, even with the ongoing digitalization of and enhancements in infrastructure. This analysis emphasizes the key issues from the perspective of regional and global best practices.

- Lack of Cohesive Coordination Among Institutions: Several border agencies operate at the Torkham BCP, each possessing overlapping responsibilities and exhibiting limited coordination. The absence of a centralized Border Authority or designated lead agency leads to procedural duplication in border trade, inconsistent law enforcement, and avoidable delays in cargo clearance and passenger processing.

- Fragmented and Inconsistent Digitalization: E-portals, including PSW, Web-Based Customs (WeBOC), and National Terminal Operating System (NTOS), have been introduced to provide enhanced online documentation and payment functionalities. However, the integration among all agencies at Torkham is not fully realized, and several processes still require the submission of physical documents. The BCP is currently facing challenges with unreliable high-speed data connectivity, attributed to frequent outages of the existing aerial cables. The situation underscores the necessity of an underground fiber-optic network to guarantee consistent and stable digital operations.

- Insufficient Infrastructure and Facilities: Despite ongoing infrastructure upgrades aligned with the international standards, traffic and cargo congestion continue to be a key challenge due to limited BCP capacity, narrow roads, and insufficient inspection bays. Parking areas and scanning equipment frequently experience underutilization, and traffic flow management tends to be less than optimal, particularly during peak hours.

- Underutilized Risk Management and Pre-arrival Processing: The risk management systems (RMS) are integrated within the WeBOC, enabling targeted inspections and supporting prearrival processing. Nevertheless, their practical application continue to be limited, with numerous traders either lacking awareness of or facing challenges in accessing these key resources. Almost all cargo consignments continue to undergo routine inspections, which diminishes the port efficiency advantages of the selectivity tools.

- Limited Utilization of Digital Payment Systems and Trade Facilitation Instruments: While PSW and NTOS provide digital payment options, manual and cash transactions continue to be used. This is generally observed when traders make payments for terminal and inspection fees. Ensuring advocacy and sound implementation of digital payment systems aimed at traders, cargo and logistics providers and small and medium-sized enterprises is critical.

- Security Constraints and Operational Disruptions: Regional security impediments lead to sudden and random closures and restrictions, adversely affecting local and regional trade reliability. These closures also cause major supply chain disruptions and increase logistics costs.

- Low Participation of Key Stakeholders and Absence of Procedural Transparency: Logistics operators, including traders and freight forwarders, indicate a minimal involvement and participation in policy building or reforms implementation. The lack of communication of changes in procedural operational information increases uncertainty, and hampers trust and compliance.

To improve trade facilitation, security, and operational efficiency of the Torkham BCP, the following recommendations, structured on international best practices and regional experiences across CAREC members, are proposed.

Recommendations

- Establishing a Coordinated Border Management (CBM) Framework: Based on the significance of Torkham and other BCPs connecting Central Asia, a designated border management agency or authority may be established to streamline BCP operations, oversee joint inspections, and improve interagency coordination. In terms of best practices, the existing Kazakhstan–China Khorgos BCP Joint Border Commission may serve as a foundation model.

- Fully Operationalize E-Platforms: Though Pakistan has made considerable progress in developing E-platforms such as PSW, WeBOC, and NTOS, their complete integration at the BCPs, including Torkham, is still ongoing. For optimal utilization, all border agencies at Torkham must be fully affluent with these e-platforms. More focus on user training, data exchange among key border-crossing stakeholders, and sound internet infrastructure should be prioritized. To enhance these e-platforms, case studies of Singapore’s TradeNet and Azerbaijan’s ASYCUDA systems may be considered.

- Optimal Utilization of Upgraded Infrastructure: While the BCP infrastructure is being upgraded at Torkham, continuous monitoring of the newly designed facility must be conducted. The facility must provide expanded inspection areas, state-of-the-art cargo scanners, and distinct lanes for cargo and passenger movement. Strong focus should be placed on the infrastructure for implementing the operational protocols for maintenance, training, and staffing.

- Risk-Based Inspections and Pre-arrival Processing: It is recommended to implement and enhance the usage of RMS modules with the existing WeBOC system to ensure their consistent application by customs and quarantine agencies. Awareness campaigns for traders and other key stakeholders may be initiated to promote prearrival document submission.

- Ensure Universal Adoption of Digital Payment Systems: Institutionalize the use of PSW and NTOS digital payment gateways for all duties, terminal fees, and inspection charges. Monitor compliance and support smaller traders through capacity-building and fallback payment channels. Pakistan can learn from Rwanda’s mobile-based e-payment system, which increased transparency and reduced time for cross-border payments in the country.

- Enhance Security and Business Continuity Planning: Complement existing non-intrusive inspection (NII) equipment with formal contingency plans for temporary closures and disruptions. Use real-time monitoring tools to maintain operations during security-related events. The Alashankou–Dostyk BCP (China–Kazakhstan) is a good example to follow, as it balances enforcement with facilitation through RMS and NII, maintaining trade flows during regional volatility.

- Improve Stakeholder Engagement and Transparency: Institutionalize regular public–private dialogue mechanisms involving transporters, traders, and logistics operators. Ensure all procedural changes, estimated processing times, and contact points are made available online and updated regularly.

- The data on capacity was obtained through a special survey commissioned by ADB in 2024 to supplement the CPMM work. This survey was implemented by the CPMM partners on Torkham to collect qualitative and quantitative information on the BCP. ↩︎