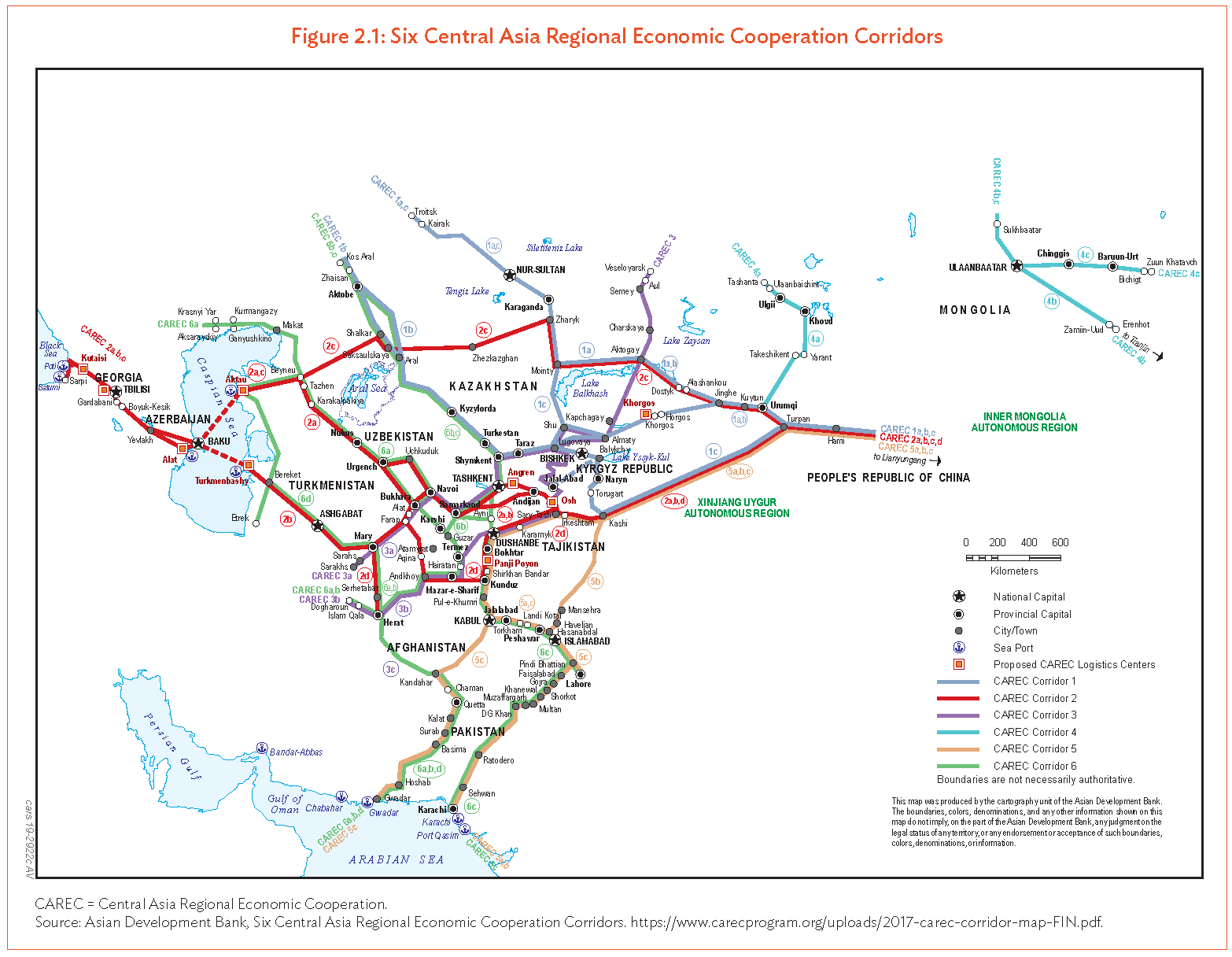

This chapter is a new addition to the CPMM Annual Report 2023 to highlight important and interesting developments in new and existing transport routes in CAREC. ADB established six routes collectively known as the CAREC Corridors (Figure 2.1). These were first conceived in 2005 based on a variety of factors and have been periodically revised since to include new routes. For example, Corridor 2 was extended to include Georgia after its entry into CAREC, and now serves as an important reference for analyzing the Middle Corridor. Other ongoing exciting developments in the region are elaborated in the subsequent sections.

Table 2.1: Summary of Key CAREC Transport Routes (2023) [1]

| Route | CAREC Countries | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Middle Corridor (TITR) | Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Turkmenistan | This multimodal corridor connects East Asia to Europe via Central Asia and the Caspian Sea, bypassing Russia. Traffic surged by 86% in 2023, but capacity constraints emerged at ports (Aktau and Alat) and BCPs (Tsiteli Khidi and Krasnyi Most). The 2022–2027 roadmap covers upgrading infrastructure and harmonizing procedures. |

| PRC–Kyrgyz Republic–Uzbekistan Railway | PRC, Kyrgyz Republic, Uzbekistan | This is a planned 486-km railway, with $4.6 billion of funding and expected to transform Central Asia’s access to PRC. Most of the route passes through Kyrgyz Republic. Once operational, it will serve the Fergana Valley and connect to PRC’s rail grid via Kashgar. |

| Pakistan–Afghanistan–Uzbekistan Railway | Pakistan, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan | The trilateral 760-km rail project to connect Tashkent to Peshawar via Kabul and Torkham aims to carry up to 15 million tons (mt) annually by 2030. The route offers Central Asia direct access to ports in Pakistan, shortening access to maritime trade and Middle East markets. |

| Shymkent–Tashkent–Khujand Economic Corridor (STKEC) | Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan | The corridor is a subregional initiative to integrate the cities of Shymkent, Tashkent, and Khujand through trade, logistics, and industrial cooperation. In 2023, a joint ICIC facility was discussed with 63 co-investment projects and support for priority industries such as food, textiles, and pharmaceuticals. |

| Almaty–Bishkek Economic Corridor (ABEC) | Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic | This pilot economic corridor will link Almaty and Bishkek to develop shared services in tourism, healthcare, and agriculture. In 2023, bilateral meetings reaffirmed the joint commitment to infrastructure planning and economic integration. |

| PRC–Mongolia Route | PRC, Mongolia | The Tianjin–Zamiin-Uud–Ulaanbaatar corridor saw worsening rail congestion in 2023. Zamiin-Uud’s limited capacity (7 trains/day) contrasts sharply with Tianjin and Erenhot’s handling capability. Long delays led to increased use of costly road transport via a newly modernized truck terminal. |

| China–Europe Container Block Trains (CRE) | PRC, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, Russia, Belarus, Europe | The CRE network grew to 17,523 trains and 1.9 million TEUs in 2023, linking 110 PRC cities to over 200 European ones. Delays at gauge change points (e.g., Dostyk and Brest) and uneven adoption of electronic data systems remain bottlenecks, though digital trade facilitation efforts are underway. |

| Baku–Tbilisi–Kars (BTK) Railway | Azerbaijan, Georgia, Türkiye | This is a strategic rail line linking the Caspian Sea to Europe without crossing Russia. After year-long renovations, full service resumed in 2024. It integrates with the Middle Corridor and targets a 5–17 mt capacity. Gauge-change delays at Akhalkalaki remain a constraint. |

The review of individual routes provides the following insights that highlight the trends of 2023.

Redirection of Transit and the Rise of the Middle Corridor

The Russia–Ukraine conflict continued to reconfigure Eurasian freight flows, catalyzing a second consecutive year of growth for the Middle Corridor (Trans-Caspian International Transport Route). The route, which bypasses Russian territory, gained momentum as international shippers sought alternative paths to Europe. Cargo volumes surged 86% year-on-year, confirming the Middle Corridor’s growing strategic importance.

However, the increase brought unintended stress across key nodes. Seaports such as Aktau, Kuryk and Alat faced capacity bottlenecks, while border-crossing points such as Tsiteli Khidi (Georgia) and Krasnyi Most (Azerbaijan) were overwhelmed. At Tsiteli Khidi, average crossing times more than doubled owing to throughput mismatches with downstream nodes and a surge in road permits required for transit traffic. To become a viable alternative, the Middle Corridor has to overcome limitations in port infrastructure, interoperability, and coordinated customs regimes.

Railway Expansion as a Strategic Tool

The geopolitical urgency to diversify trade corridors also reignited interest in rail connectivity. The following two significant developments stood out in 2023:

- The 486-km PRC–Kyrgyz Republic–Uzbekistan railway was formally agreed upon and financed

last year. Representing more than physical infrastructure, it is a long-anticipated pivot for Central

Asia to tap into PRC’s domestic markets and logistics capacity. The rail line aims to link Central

Asia’s heartland to PRC without routing through Kazakhstan, thereby easing pressure on northern

gateways like Dostyk and Alashankou. - The Pakistan–Afghanistan–Uzbekistan railway project advanced after a trilateral protocol to connect Tashkent to Peshawar via Kabul. When complete, it would open up southern maritime access to Central Asia through Pakistani ports, namely Karachi, Gwadar, and Port Qasim. This new route offers shorter and cheaper alternatives to Tianjin or Black Sea routes. These projects indicate a strategic rebalancing of regional access by shifting from dependency on Kazakhstan and Russia to a multi-vector approach involving PRC, Pakistan, Türkiye, and the Caspian Sea routes.

These projects indicate a strategic rebalancing of regional access by shifting from dependency on Kazakhstan and Russia to a multi-vector approach involving PRC, Pakistan, Türkiye, and the Caspian Sea.

Growing Strain on Legacy Infrastructure

While new corridors were being planned, legacy infrastructure struggled to keep pace with volume spikes and modernization needs. The China–Europe block train network (CRE), with over 17,500 trains and 1.9 million TEUs in 2023, highlighted both success and stress. Key transshipment points such as Dostyk, Altynkol, and Khorgos continued to face delays from change-of-gauge operations and insufficient container handling capacity. Despite progress in digitalization and harmonization, the 24–48 hr transloading delays remained unresolved, underscoring the need for smart logistics systems rather than just physical infrastructure.

At the same time, Zamiin-Uud in Mongolia became emblematic of systemic rail bottlenecks. Designed to handle just seven trains a day, it received heavier traffic from PRC ports capable of dispatching 45. The result was severe congestion, with delivery times lengthening from 14 days to over three months. This logistical gridlock forced many Mongolian shippers to revert to expensive road transport to maintain supply chain continuity, an ironic reversal in modal shift amid a containerization push.

Urban Corridors as Economic Clusters

Another emerging trend is the pivot from linear transport corridors to urban economic corridors, particularly in more densely populated areas. The Shymkent–Tashkent–Khujand Economic Corridor (STKEC) and Almaty–Bishkek Economic Corridor (ABEC) exemplify this shift. These initiatives are no longer just about improving transport; they aim to create regional production hubs and logistics catchment areas, with joint industrial parks, logistics centers, and harmonized regulation to attract trade and investment. ADB’s support for the ICIC (International Centre for Industrial Cooperation) near Atameken-Gulistan, and upcoming Trade and Logistics Centers in Khujand, marks a new direction where connectivity serves industrialization, not just transit.

Policy Gaps and Structural Fragility

Despite an ambitious infrastructure pipeline, the year 2023 exposed chronic policy mismatches. Customs harmonization remains patchy. Gauge differences, transloading protocols, and divergent SPS standards continue to constrain seamless trade. A case in point is Khorgos, one of the busiest BCPs in the region that still lacks synchronized inspection systems between PRC and Kazakhstan. Similarly, the BTK rail line, an anchor of the Middle Corridor, resumed services in 2024, but still faces challenges at Akhalkalaki due to gauge conversion inefficiencies and fragmented digital tracking. Moreover, the lack of digital integration across many BCPs remains a thorny issue. The success of the Pakistan Single Window and Georgian E-clearance initiatives heavily contrast with the manual inspection regimes, plagued by time- consuming and corruption-prone procedures, in places such as Chaman or Torghondi.

[1] Refer to Appendix 1 for the details of each route.