The CPMM analysis relies on consistent and comparable data across CAREC countries, despite their inherent differences. This chapter provides an update of the main developments and CPMM data at a national level for each CAREC member country to help explain the trends or resulting outcomes at the regional or corridor level. This country-level analysis examines the policies, regulations, infrastructure, and institutional factors that can affect corridor performance. Pertinent barriers and issues are highlighted, key developments and progress are noted, and high-level recommendations are included.

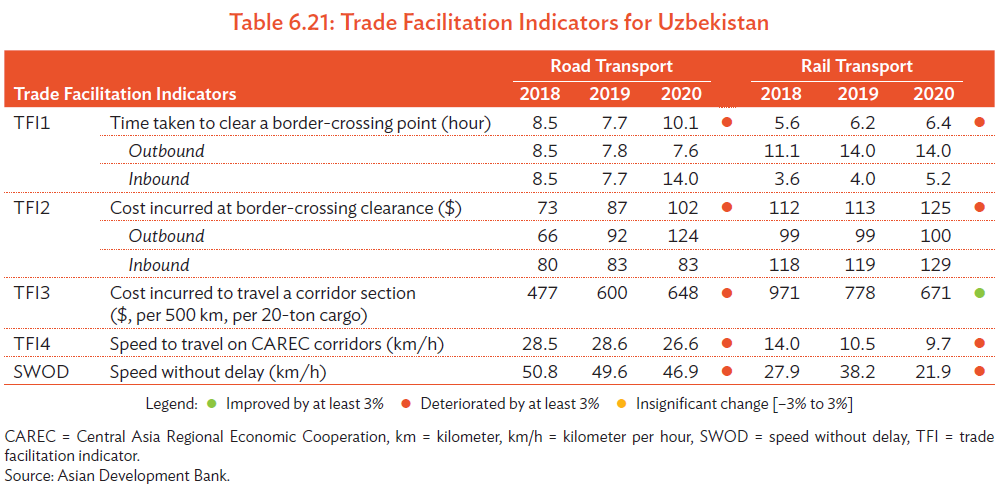

The 2020 CPMM report introduces the four TFIs at the country level, segregated by road and rail transport, and further separated into outbound and inbound direction for border-crossing time and costs (Tables 6.1–6.22). These data are supplemented by average border-crossing time and cost for BCPs along relevant CAREC corridors. Key CPMM findings, updated trends and developments, and country-specific recommendations are also provided in this chapter.

Key Findings

- In 2020, border-crossing time for road transport jumped from 7.7 hours in 2019 to 10.1 hours in Inbound vehicles had to undergo prolonged inspection time due to strict sanitation and health controls.

- Border-crossing cost increased from $87 in 2019 to $102 in 2020. Total transport cost also increased from $600 in 2019 to $648 in 2020.

- Both SWOD and SWD for road transport showed a dip, reaching 46.9 km/h and 26.6 km/h, respectively in 2020.

- For rail transport, border-crossing time was little changed from 6.2 hours in 2019 to 6.4 hours in 2020.

- Border-crossing cost increased from $113 in 2019 to $125 in 2020. Total transport cost decreased from $778 in 2019 to $671 in 2020. Since border-crossing cost increased yet the total transport cost decreased, it could be inferred that rail freight rate in Uzbekistan decreased.

- Both SWOD and SWD for rail transport showed a dip, reaching 21.9 km/h and 9.7 km/h, respectively, in 2020.

- Road BCPs such as Yallama (30 hours), Saryasia (25.7 hours), and Dautota (14.3 hours) topped the list of most time-consuming BCP in Uzbekistan. For rail transport, Keles reported 72 hours of border delays.

Trends and Developments

Notable progress was made in rail connectivity. On 5 June 2020, Lanzhou, the provincial capital of Gansu Province in the PRC, inaugurated a multimodal express container rail service to Tashkent. This route passes through Kashgar (Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region in the PRC), Osh (Kyrgyz Republic), and Andijan (Uzbekistan). The Uzbek–Chinese joint venture company Silk Road International Ltd. transports containers over the road from Kashgar to Osh rail station in the Kyrgyz Republic. At Osh, the containers are loaded by KTJ (Kyrgyz Railway) into platform wagons to form a block train connecting to UTY (Uzbekistan Railway). Moreover, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Uzbekistan conducted a series of negotiations to put in a trilateral agreement a railway link from Uzbekistan to Pakistan across Afghanistan, terminating in Peshawar, Pakistan near the Torkham BCP.

COVID-19 has impacted the Uzbek road transport sector negatively, causing some carriers to suffer financial difficulties. When the pandemic struck, Uzbekistan closed its border on 15 March 2020 after the first COVID-19 case was detected. It has subsequently reopened its border to freight traffic under strict health and quarantine controls. All drivers (national or foreign) must pass a COVID-19 testing procedure, which takes about 14–16 hours for the results. There is no charge for such test. Drivers stay at special Uzbek parking areas near BCPs while awaiting test results. Basic services are provided to drivers and special personnel with access to such areas. If the test result is positive, the driver will be quarantined until the actual infection status is confirmed or after full recovery. Only healthy drivers are allowed to enter the country. Additional time and cost associated with enhanced health screening, quarantine, and sanitization have increased the operating costs of Uzbek carriers, while the demand and supply imbalance prevent them from passing the cost increases to shippers, squeezing their already thin profit margins.

On a positive note, Uzbekistan has continued its customs reform by adopting international customs standards and implementing good practices. The registration of the cargo declaration is being simplified and risk management system has been introduced at road BCPs. The State Customs Committee reported the following progress:

- Average time for customs export clearance reduced from 2 hours 16 minutes to 44 minutes.

- Average time for customs import clearance decreased from 6 hours and 44 minutes to 2 hours 34 minutes.

- 22.7% of goods moved through the green corridor and 39% of goods through the yellow corridor.

Recommendations

- Install modern scanners to expedite inspection of vehicles and cargoes. Current border delays were attributed to a shortage of equipment and many “human touchpoints.” For instance, by using automated weight machines, high speed scanners, and online video surveillance systems to improve border operations, the throughput of the vehicles could be increased.

- Increase the number of access roads to border-crossing points. Currently, the traffic flow of vehicles into and out of the BCPs is hampered by limited access roads and causes difficulty in separating the flow of traffic or segregating human and vehicular traffic. It is recommended to have at least three lanes in one direction to improve the accessibility of the BCPs.

- Mandate a time limit for border clearance. Using risk-based management, any shipment that is determined to be in the green channel (no signals of violations) should be crossing a BCP within 30 minutes from the time of arrival at the gate.

- Develop roadside facilities and services for drivers. Since adopting a liberalization drive, Uzbekistan has attracted transit traffic. This is evident in the rapidly increasing number of TIR Carnets issued from International Road Transport Union (IRU) to AIRCUZ, the national TIR association in the country.36 These should include facilities such as cafe, motel, hostel, secure parking areas, and maintenance and repair services for international drivers at the main international routes or corridors with compliant sanitary procedures. The locations of such facilities and services could also be published on maps and on the internet.

- Negotiate with Turkmenistan and Iran on controls. Uzbek operators requested for clear and coordinated communications between countries on the implementation of sanitation and health measures to avoid incidents of trucks being detained unnecessarily due to unclear policies and procedures, which happened when they traversed Turkmenistan and Iran. Closures of certain BCPs and road sections could result in the collapse of an important trade corridor, which would be particularly detrimental to double landlocked Uzbekistan that relies on these neighbor countries to access seaports and overseas markets.

- Provide higher priority to freight trains. To promote tourism, passenger traffic currently enjoys higher priority over rail traffic when train paths are assigned. As rail cargo is far more profitable to UTY than passengers, the government should allow UTY to gradually assign parity to rail freight traffic to drive higher income.