Trade Facilitation Indicators

On a year-to-year comparison, the 2020 CPMM data showed that

- average border-crossing time increased from 12.2 hours in 2019 to 15.1 hours in 2020;

- border-crossing cost increased from $161 in 2019 to $199 in 2020;

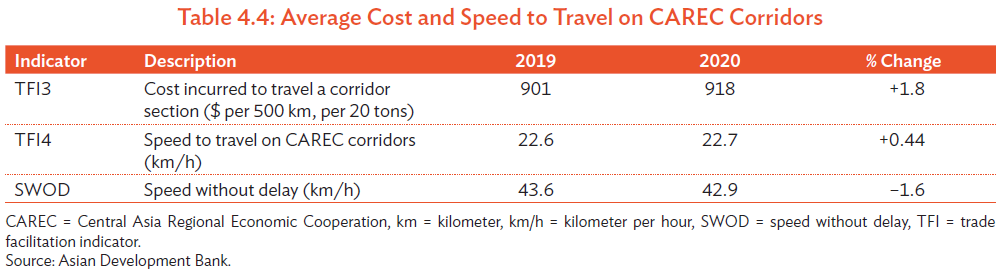

- total transport cost to travel a corridor section increased from $901 in 2019 to $918 in 2020; and

- SWD remained relatively unchanged from 22.6 km/h in 2019 to 22.7 km/h in 2020, while SWOD

- decreased slightly from 43.6 km/h in 2019 to 42.9 km/h in 2020.

Trade facilitation indicators in 2020 for road transport are summarized in Tables 4.1 and 4.4. Results for

TFIs by corridor are provided in Appendix 6.

Trade Facilitation Indicator 1: Average Border-Crossing Time

In 2020, CPMM data identified lengthy border-crossing times for road transport at Chaman (70.7 hours), Kuryk (69.7 hours), and Torkham (50.0 hours), for outbound traffic. These three BCPs also occupied the top three ranks in the same order in 2019, but the average time in 2020 was noticeably larger. For inbound traffic, the most time-consuming BCPs were Yallama (30.0 hours), Saryasia (25.7 hours), and Torkham (4.2 hours).

All corridors showed an increase in TFI1 except Corridor 6, which reported a slight decrease. Corridor 5 was the most time-consuming at 40.2 hours, up from 28.0 hours in 2019 as extended border closures, additional sanitation controls, and the already lengthy waiting time affected drivers. Corridor 6 was the next highest at 13.5 hours, followed by Corridor 2 at 10.6 hours. The shortest time was observed at Corridor 4 at 6.3 hours.

Trade Facilitation Indicator 2: Average Border-Crossing Cost

A principal cause that drove the sizable cost increase was due to elevated fees at Corridor 1. Trucks crossing BCPs at the PRC–Kazakhstan border had to pay substantially higher fees, from $173 in 2019 to $638 in 2020, an increase of 3.7 times, due to COVID-19 measures resulting in materials transfer as cargoes are unloaded and then reloaded onto different vehicles to contain the spread of the virus. The materials transfer at the BCPs became more cumbersome and would be elaborated on in the subsequent Corridor 1 discussion.

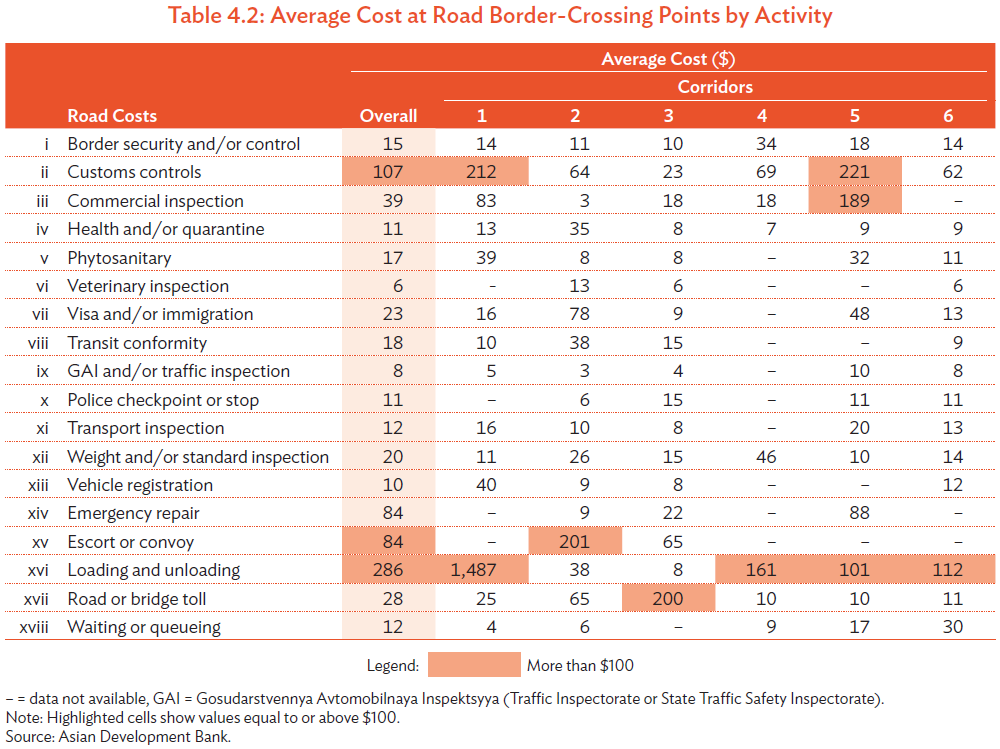

Table 4.2 illustrates the dispersion of costs incurred at BCPs along CAREC corridors in 2020. The major payments were loading and unloading and customs controls. Traditionally, the loading and unloading cost at Corridor 1 would be the most expensive activity and cost $316 on average, but for the first time it hit $1,487 in 2020. Corridors 4, 5, and 6 all reported an increase for loading and unloading as well, suggesting that border measures such as sanitation and quarantine might lead to mandatory transfer of freight from a foreign truck to a local truck to minimize risks of cross-contamination.

The CPMM analyzed unofficial payments in CAREC region (Table 4.3).15 The same rent-seeking behaviors were observed during 2018 and 2019 in the following activities, ranked by likelihood of occurrence: (i) vehicle registration (48%), (ii) phytosanitary activities (28%), (iii) customs controls (24%), (iv) transport inspection (21%), and (v) weight and standard inspection (18%). All these top five activities reported a decrease in the probability of informal payment in 2020 compared to the previous year. In terms of the magnitude of unofficial payment per truck, the largest sums were taken at (i) loading and unloading ($212), (ii) waiting time ($212), (iii) customs controls ($126), escort and convoy ($83), and (v) road toll ($83). The estimated informal payment amount doubled in 2020 for loading and unloading, which happened after June when borders opened and merchandise production ramped up, leading to increased cross-border trade. Increased informal payment was also seen at waiting time. This showed that transport operators increased the informal payment to complete border crossing faster. On the other hand, transport operators shared that at the beginning of the pandemic when many border officers had to return home or work from home, informal payment was actually less. This showed that reducing the number of human interventions in a process could be helpful to manage informal payment. This could be achieved when digitalization and digital tools are adopted to automate processes.

Trade Facilitation Indicator 3: Total Transport Cost

The average total transport cost to travel a corridor section increased from $901 in 2019 to $918 in 2020. The picture for this indicator is not straightforward due to two counteracting factors. While road freight rates increased due to the difficulty of finding available capacity, particularly in the first half of the year during the pandemic outbreak, government interventions helped to reduce some of the increases in operating cost (e.g., driver shortage) due to COVID-19. For instance, the PRC government eliminated toll fees for a limited period while other countries provided various support measures. Corridor 1 had the highest cost at $1,788 in 2020, from $1,092 in 2019. Corridors 3 and 4 likewise increased at a smaller magnitude but the other corridors decreased.

Trade Facilitation Indicator 4: Speed to Travel on CAREC Corridors

Corridor 1 remained the fastest corridor for trucks, reaching average speeds of 69.5 km/h, followed by Corridor 2 at 46.6 km/h. Slowest SWOD occurred at Corridor 5 at 28.4 km/h. In terms of SWD, Corridor 1 remained the fastest (41.1 km/h), followed by Corridor 2 (24.7 km/h). Corridor 5 posted as the slowest at 8.6 km/h.

Corridor Performance

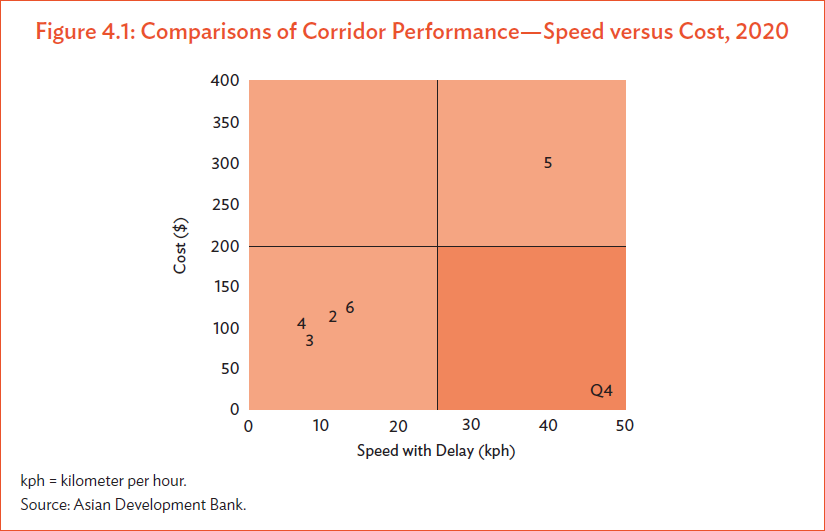

Figure 4.1 shows the relative performance of the six CAREC corridors using SWOD and border-crossing cost. The numbers in the matrix represent the CAREC corridor identifier (CAREC corridor 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6). Corridor 5 is seen to have the highest relative time and cost, continuing this trend for the 7th year.

Corridor 1—Road

As the main route for East Asia–Central Asia trade, Corridor 1 serves a substantial trade volume between the Central Asian republics and the PRC. Horgos–Nur Zholy (PRC–KAZ)17 handles the dominant proportion of road freight and for this reason, the first TIR shipment from Germany to PRC in 2019 passed through this BCP.18 In 2020, trucks spent more time to cross-border at Alashankou–Dostyk (PRC–KAZ) at subcorridor 1a, while trucks paid more in fees at Horgos–Nur Zholy at subcorridor 1b.

The high fees particularly at Horgos–Nur Zholy were partly due to informal payments under the guise of formal border procedures. Transport operators had to pay additional fees to so-called customs brokers to facilitate border-crossing or suffer extended questionings and place last in the queue for inspection and processing. As a rule, transport inspection and Gosudarstvennya Avtomobilnaya Inspektsyya (GAI, the Traffic Inspectorate or State Traffic Safety Inspectorate) unofficial fees were small, while customs formalities incurred higher amounts. Also, the size of the unofficial fees varies according to the nature of the cargoes. Time-sensitive items and dangerous goods are more expensive than general cargoes due to the time urgency or the higher complication of securing the permits to transport dangerous goods.

In November 2020, the PRC mandated a new rule that resulted in a sharp increase in border-crossing cost. Kazakhstan registered trailers and trucks that formerly could enter bonded warehouses at the PRC Horgos BCP are no longer permitted entry. A delivery truck from Urumqi or inland Chinese cities would terminate at Horgos and off-load the goods to a temporary bonded warehouse. The warehouse workers will disinfect the goods, palletize (if necessary), and then cover the goods with a stretch wrap to secure the pallet and the goods on it. A forklift is then used to move the pallet onto a trailer that is hauled by an authorized carrier to enter “no man’s land” between Horgos in the PRC and Nur Zholy in Kazakhstan. Over there, another fleet of forklifts and forklift drivers stand by to transfer the materials from the Chinese trucks to the Kazakhstan trucks or trailers. This measure minimizes potential COVID-19 virus contamination but adds significant costs19 and delay to the transportation. The same procedure is observed at the PRC–Mongolia BCPs.

Toward the end of 2020, a revised procedure to address the high cost of this method was implemented. This involved elimination of stretch wrapping and use of special high-capacity trailers (which can carry more cargo) to deliver goods directly to KAZ bonded warehouses. Unfortunately, the freezing temperature prevented the spray of disinfectants to meet health control requirements for the return of these shuttle trailers to Horgos. By April 2020, over a thousand shuttle trailers were stranded in Khorgos.

Corridor 2—Road

Corridor 2 links the economies of East Asia to Central Asia, the Caucasus, and the Mediterranean via the

four subcorridors, all of which start in the PRC and ultimately link to Georgia (subcorridors 2a, 2b, and 2c)

and Iran (subcorridor 2d).

Shipments of equipment, machinery, pharmaceuticals, and processed food were transported from Poti to Central Asia in 2020. All shipments used TIR and were rarely containerized. Table 4.5 shows time and cost indicators for a sample of shipments of noncontainerized cargo on trucks from Poti seaport to Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan, crossing the Caspian Sea via seaports in Baku and Kuryk. Shipment time is estimated to be 10 days to Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, and 13 days to Kazakhstan and the Kyrgyz Republic. Approximately half of the total shipment time was spent at Baku–Kuryk to cross the Caspian Sea, due to waiting time for vessels, obtaining entry permission, insurance, disinfection of trucks, and COVID-19 testing of the drivers. Road freight cost ranged from $1,800 to $2,150. Additional fees were applied through the typical customs and border processing as well as a series of road tolls. Heavy equipment and high-value items20 were subject to customs escort and special permit, which add another $200 in fees. Unofficial payments were detected at Kuryk for weight inspection ($100) and at Tazhen under customs control ($20–$30).

Corridor 3—Road

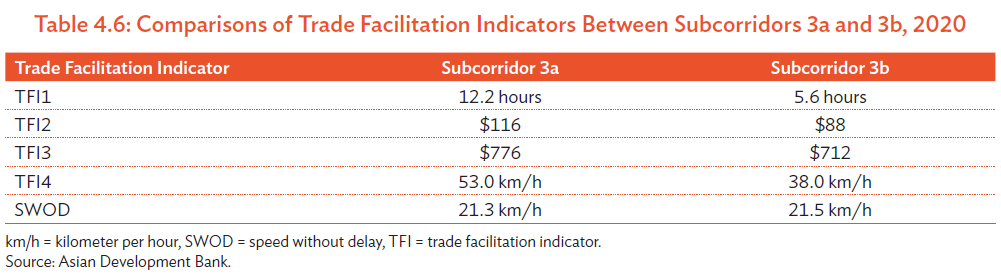

This north–south corridor links the eastern part of the Russian Federation to the Middle East through Central Asia. The northern section in Kazakhstan splits into two at Merke: section 3a moves into Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, ending in Iran; and section 3b heads south to the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, and Afghanistan, also ending in Iran.

In 2020, border-crossing at subcorridor 3a took a longer time and higher fees (Table 4.6). Although trucks could travel at 53 km/h on subcorridor 3a compared to 38 km/h on subcorridor 3b, the SWDs were relatively similar as longer border-crossing time impacted the values, leading to similar SWDs. The average border-crossing in subcorridor 3a such as Yallama–Konysbaeva (Uzbekistan [UZB]–KAZ), Alat–Farap (UZB–Turkmenistan [TKM]), and Sarahs–Sarakhs (TKM–Iran [IRN]) had higher average values compared to the BCPs in subcorridor 3b such as Karamyk (Kyrgyz Republic [KGZ]–Tajikistan [TAJ]) and Dusti/Pakhtaabad–Saryasia (TAJ-UZB).

The COVID-19 pandemic led to more stringent controls in cross-border trade, and this was also evident in Corridor 3. Generally, inbound traffic tends to require more time due to disinfection, testing, and quarantine compared to outbound traffic. Health and quarantine checks that took 10–20 minutes in the past now increased substantially. For instance, this activity took 26 hours at Yallama and 16 hours at Saryasia.

Corridor 4—Road

This trilateral corridor connects Mongolia to the Russian Federation in the north, and to the PRC in the south, and is both a trade and transit corridor vital to the economy of Mongolia. Among the three routes, subcorridor 4b is most important as it serves both road and rail transport. The Erenhot–Zamiin-Uud (PRC–Mongolia [MON]) BCP is a key gateway for cross-border trade, allowing Mongolia to access the Tianjin seaport in the PRC.

Subcorridor 4a is a passageway for export of coal from Kexuete to the PRC, passing through Takeshikent– Yarant (PRC–MON) BCP. For part of 2020, Mongolia closed the BCPs to trucks delivering goods from the PRC to interior Mongolian destinations. A new development in 2020 was the noticeable increase of border-crossings at Takeshikent (31.8 hours). Since October 2020, a new transfer of trailers to minimize human contact was instituted at the PRC BCPs including Takeshikent. First, Mongolian transport operators sent a Mongolian registered empty trailer to a designated section in the “no man’s land,” which is a buffer zone between the borders of the two countries. The Chinese transport operator retrieved the empty trailer back to a bonded warehouse for the loading of goods under customs supervision. The loaded trailer was then positioned at the “no man’s land” for the Mongolian transport operator to pick up and return to Mongolia. This additional step took 30–40 hours and added $63421 to the overall border-crossing cost.

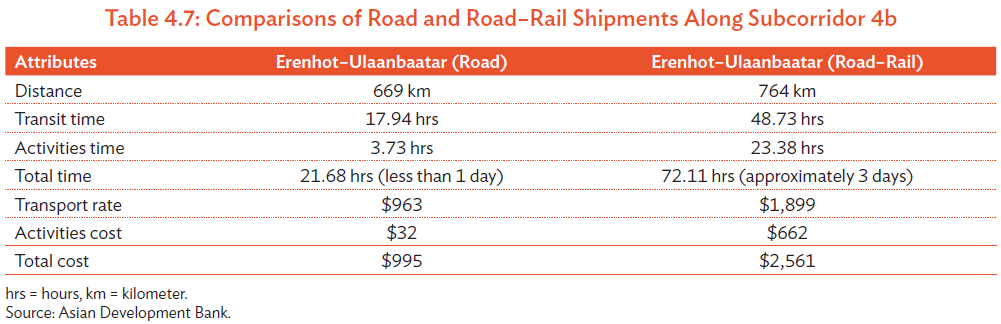

Subcorridor 4b is a multimodal corridor. Shippers have two means to send freight from Erenhot to Ulaanbaatar. A shipment by truck was faster and costs less in absolute terms, which also offers flexibility as some cargoes such as certain categories of dangerous goods are prohibited to be transported on railways. For road–rail shipment, the main delay at Erenhot is the transfer of cargo from truck to wagons, which took 4–5 hours (Table 4.7). Customs, commercial inspection, and health or quarantine measures took 1–2 hours each. Despite the apparent longer time and higher cost, the road–rail option is still used because this method offers better protection and security to the cargo and less likelihood of damage in transit. This is an important consideration especially for high-value equipment and machinery for instance.

Subcorridor 4c also catered to bilateral trade through Zuun Khatavch–Bichigt (PRC–MON) where traffic is much lighter compared to Erenhot–Zamiin-Uud. However, this BCP pair was closed to freight transport beginning March 2020.

Corridor 5—Road

Corridor 5 connects Central and East Asia to South Asia, providing potential routes to access all-weather seaports at Karachi, Pakistan for the landlocked countries. Three subcorridors traverse from the PRC and the Central Asian republics in the north toward Afghanistan and Pakistan, terminating at Karachi, and the new seaport Gwadar.

As with previous years, Corridor 5 was the most time-consuming to cross borders, as well as the slowest corridor for trucks to move. When news of COVID-19 spread across the world, BCPs were closed abruptly; Afghanistan and Pakistan restricted border operations in April; and BCPs opened only for 3 days a week. Restrictions were subsequently loosened, and borders operated 5 days in May to June. By end of June, all BCPs operated 6 days a week, closed only on Saturday but remaining open to allow passenger movements only.

The impact of the border closures resulted in a sharp increase in delays at Torkham. A backlog of containerized goods from Karachi queued at Torkham. The situation worsened in the second quarter (Q) of 2020 as local civil unrest near Chaman led to the closure of Chaman BCP. Thus, trucks carrying containers bound for Afghanistan had to divert to Torkham, adding to the already long queue there. Border-crossing time only normalized in Q4 2020.

Corridor 6—Road

Like Corridor 5, Corridor 6 serves interregional transit trade between Central and South Asian economies with the Caucasus, Middle East, and the Russian Federation. Uzbekistan operators actively use Corridor 6 to move goods to the Russian Federation, and Pakistan agricultural producers ship their products to Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan.

Subcorridors 6a and 6b were used actively by Uzbek transport operators to move agricultural products to the Russian Federation, where Kazakhstan serves as a transit country. In return, consumer and industrial products were exported. Subcorridor 6a had an average border-crossing time of 8.7 hours, border-crossing cost of $67.90, total cost of $585, and SWOD of 47 km/h. Dautota–Tazhen (UZB–KAZ) is the BCP for this route, and the times to cross border were estimated to be 8.1 hours for Dautota and 7.3 hours for Tazhen. Kurmangazy–Krasny Yar (KAZ–Russian Federation [RUS]) required shorter time since both the Russian Federation and Kazakhstan are founding members of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU); hence, only border and sanitary and phytosanitary inspections apply. The estimated time to cross the border was 3.3 hours to Kurmangazy, and 1.4 hours to Krasny Yar.

At subcorridor 6b, average border-crossing time was estimated at 6.1 hours, border-crossing cost at $116.50, total cost at $601, and SWOD at 38 km/h. Pakistan exports tropical fruits to Tajikistan, with Afghanistan serving as a transit country. Due to security conditions within Afghanistan, and the ongoing negotiation to conclude the stalled Afghanistan–Pakistan Transit Trade Agreement (APTTA) 2010, multiple changes of trucks are required.

At subcorridor 6c, average border-crossing time was estimated at 18.4 hours, border-crossing cost at $200.90, total cost at $757, and SWOD of 35 km/h. Like subcorridor 6b, this route was an export passageway for Pakistan to export to Uzbekistan. At subcorridor 6d, average border-crossing time was estimated at 32.7 hours, border-crossing cost at $137.70, total cost at $1,585, and SWOD at 42 km/h. Gwadar is a seaport in Pakistan located in subcorridor 6d. This seaport was permitted to handle Afghan transit trade in October 2019. It was temporarily closed due to COVID-19 but was reopened in April 2020 for Afghan transit trade. Currently, the CPMM does not capture samples from Gwadar to Afghanistan due to the small volume of freight flowing through that route.