Trade Facilitation Indicators

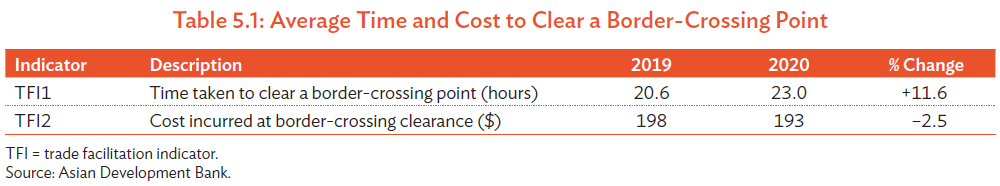

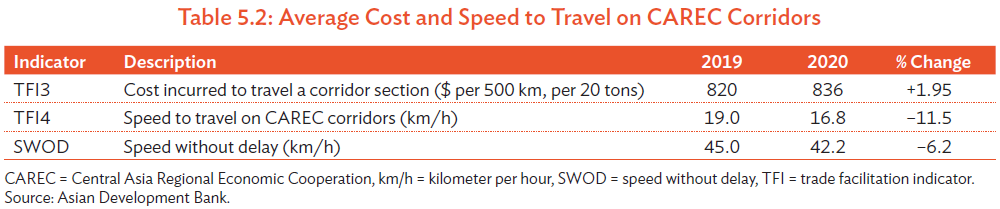

On a year-to-year comparison, the 2020 CPMM data showed that

- Average border-crossing time increased from 20.6 hours in 2019 to 23.0 hours in 2020.

- Average border-crossing costs dropped from $198 in 2019 to $193 in 2020.

- Total costs increased from $820 in 2019 to $836 in 2020.

- Average SWOD in 2020 was 42.2 km/h, a drop from 45.0 km/h in the previous year, while SWD dropped to an average of 16.8 km/h in 2020 from 19.0 km/h in 2019.

Trade facilitation indicators in 2020 for rail transport are summarized in Tables 5.1 and 5.2. Results for

trade facilitation indicators by corridor are provided in Appendix 6.

Trade Facilitation Indicator 1: Average Border-Crossing Time

The average border-crossing time dropped to the lowest in 2019, but the uptick in 2020 reached the duration estimated in 2018. Corridor 1 suffered from lengthened duration, rising from 27.6 hours to 37.3 hours over the 1-year period. Corridor 2 only had two samples, and one shipment experienced a major delay when a container on a train waited 120 hours (5 days) at Farap BCP in August 2020. Interestingly, Corridor 4 showed an improvement from 15.7 hours in 2019 to 9.1 hours in 2020. Both Erenhot and Zamiin-Uud showed shorter waiting times for wagons. One unique development was the longer time to complete sanitation controls, which used to take 10–15 minutes in 2019, but now required 1–2 hours at the major railway terminals.

Trade Facilitation Indicator 2: Average Border-Crossing Cost

Continuing the past trend, TFI2 for rail transport was steady. There was no major increase in costs despite the pandemic in 2020. Corridor 1 was the costliest section. This was due to the relatively more expensive gauge change operation and customs controls at Alashankou–Dostyk (PRC–KAZ) and Horgos–Altynkol (PRC–KAZ). Gauge change operation at Dostyk averaged $329. Corridor 4 reported that gauge change operation at Erenhot increased to $120. At Corridor 6, Torghondi (Afghanistan [AFG]–TKM) continued to report high fees for the materials transfer (loading and unloading). This is the location where goods are transloaded from Afghanistan trucks to trains bound for Turkmenistan.

Trade Facilitation Indicator 3: Total Transport Cost

The rail freight cost increased slightly due to increases across Corridors 1, 3, and 4. Corridor 6 showed a slight decrease. This reflected the strong demand for railways as a mode of transportation, which continued to operate despite the severe curtailment of road and air during the beginning of the pandemic as countries closed cross-border traffic.

Trade Facilitation Indicator 4: Speed to Travel on CAREC Corridors

Both SWOD and SWD decreased in 2020. A more severe decrease was seen at SWOD, due to the 11% increase in the average border-crossing time. It is noteworthy to highlight that despite the deterioration of speeds in 2020 on a year-to-year basis, the speeds were still above the average train speeds over a 10 year period. Better infrastructure and technologies deployed in train systems enabled a higher speed. For instance, the trains moving on the domestic network inside the PRC attained a SWOD of 120 km/h, although the SWODs estimated over all the CAREC corridors were much lower when extended to other CAREC countries.

Corridor Performance

Corridor 1—Rail

Corridors 1a and 1b serve rail freight, both regular and container express train service. Both subcorridors had an estimated average border-crossing time of 27 hours in 2019 but increased to 40.6 hours for subcorridor 1a and 31.9 hours for subcorridor 1b in 2020. Additional sanitation controls were implemented in 2020 that increased the border-crossing time. Since CPMM collection focused on rail freight from the PRC to Kazakhstan, this shall be the instance used in the following discussion on the controls adopted for rail shipments. As a general rule, the wagons and containers were disinfected at the sending rail station. A disinfection certificate was then issued, which must be presented to the sanitation and/or phytosanitary authorities at the destination. Upon satisfactory outcome, the shipment was released. If there were omissions or erroneous data, the authorities requested the consignee to furnish the necessary information or document within a specific time. Kazakhstan did not impose detention fees within the specific time. If the consignee failed to meet the dateline, the rail car or the container was dispatched to a special parking space where charges applied.

A serious delay occurred in November 2020, where more than 7,000 wagons were reported to be waiting, some more than 42 days. Chinese authorities began mandatory sanitation inspections on all containers and wagons at Chinese BCPs such as Alashankou and Horgos. Goods were unloaded and inspected and disinfected package by package. This process reduced the throughput to 11 trains per day—sometimes as low as 5 trains—below the 18 trains typical daily throughput. The freight backlog was so serious that the Government of Kazakhstan, coordinated by the Ministry of Industry and Infrastructure Development (Transport Committee), led a team of shippers and freight forwarders to Dostyk and Alashankou to negotiate a solution with the Chinese authorities. In December 2020, the throughput increased to 15 trains per day. Conventional wagons that carry agricultural produce were the most affected as most of the products have limited shelf life. Prolonged delay would affect items such as grains and oilseeds, leading to penalties imposed by the Chinese buyers on the Kazakhstan sellers if not delivered on-time, or if the quality was compromised due to excessive transit time.

Corridor 2—Rail

This corridor connects the PRC and Turkey and Southern Europe via Central Asia. Transport operators from Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Kazakhstan are promoting Corridor 2 development as a multimodal route that connects East and South Asia to the Caucasus and Europe. Currently, CPMM does not collect railways samples along Corridor 2, so no estimates could be given. One notable development was the first export train from Turkey that left on 4 December 2020 for the PRC.22 The train departed from Istanbul; moved on the Baku–Tbilisi–Kars railway; and completed the 8,693 km journey in 12 days. This achievement was an extension of the train route from the PRC to Turkey to Europe in November 2019. Railway freight service has good potential as the railway tracks extend into the key seaports in Kuryk, Baku, as well as Poti. While increased transit train activity along Corridor 2 is expected, the impediments highlighted in the CPMM Annual Report 2019 remains, such as adverse weather in the Caspian Sea that could delay vessels, high sea tariffs, high port fees, and informal payment.

Corridor 4—Rail

Corridor 4 is the Trans-Mongolian section of the Trans-Siberian Railway and in recent years has grown substantially in importance as a transit route between Europe, the Russian Federation, Central Asia, and the PRC. Subcorridor 4b is the main railway line 1,100 km long connecting the Russian Federation to the north and the PRC to the south. This single-track infrastructure has a capacity of 25 million tons per year, and trains move at a maximum speed of 80 km/h. Since Mongolia adopts a 1,520-millimeter (mm) track gauge, there is a breakage at the PRC–MON border where the receiving station performs the change of gauge operation.

In 2020, road and railways moved a similar tonnage of freight. Rail transport moved 29.84 million tons (46.88%) while road transport moved 30.45 million tons (50.51%). However, the role of rail transport was demonstrated in the major share of freight turnover, wherein rail transport moved 19.16 billion ton-km (80.33%) compared to 4.68 billion ton-km (19.64%) for road transport. Air transport moved a negligible amount of freight.

Analysis of the Erenhot–Zamiin-Uud BCP (PRC–MON) showed different border-crossing impediments. At the PRC side, inbound traffic at Erenhot took 7.4 hours, and outbound traffic 15 hours. Waiting for priority trains to pass, restriction upon entry, and marshalling were the major delay reasons. At the Mongolian side, traffic at Zamiin-Uud took 11.5 hours (inbound) and 2.1 hours (outbound). Another observation was that while change of gauge operation did not take considerable time (2.7 hours at Erenhot and 3.0 hours at Zamiin-Uud), the delay due to shortage of wagons was more serious (7–8 hours at each of the two BCPs) but still much shorter than the delays at the PRC–KAZ border.